Muzehhibe Anisa's work focuses on the ancient art of illumination, specifically Tezhip. Here, you will find its definition and historical development, along with information on traditional paints and materials used, framing methods, the production of natural aher glue, the distinctive use of gold, and a specialized gold-beating technique.

Tezhip, the traditional Islamic art of manuscript illumination, flourished notably during the Ottoman era, merging intricate compositions with the divine word to create captivating artworks. She offers commissioned pieces and shares her expertise with a broader audience

The works presented here reflect the mastery and tradition upheld by Muzehhibe Anisa, who earned this title through years of disciplined apprenticeship under a master, in accordance with Ottoman tradition. Becoming a müzehhip requires not only technical skill, but also a deep understanding of the art’s spiritual and cultural significance, passed down through generations.

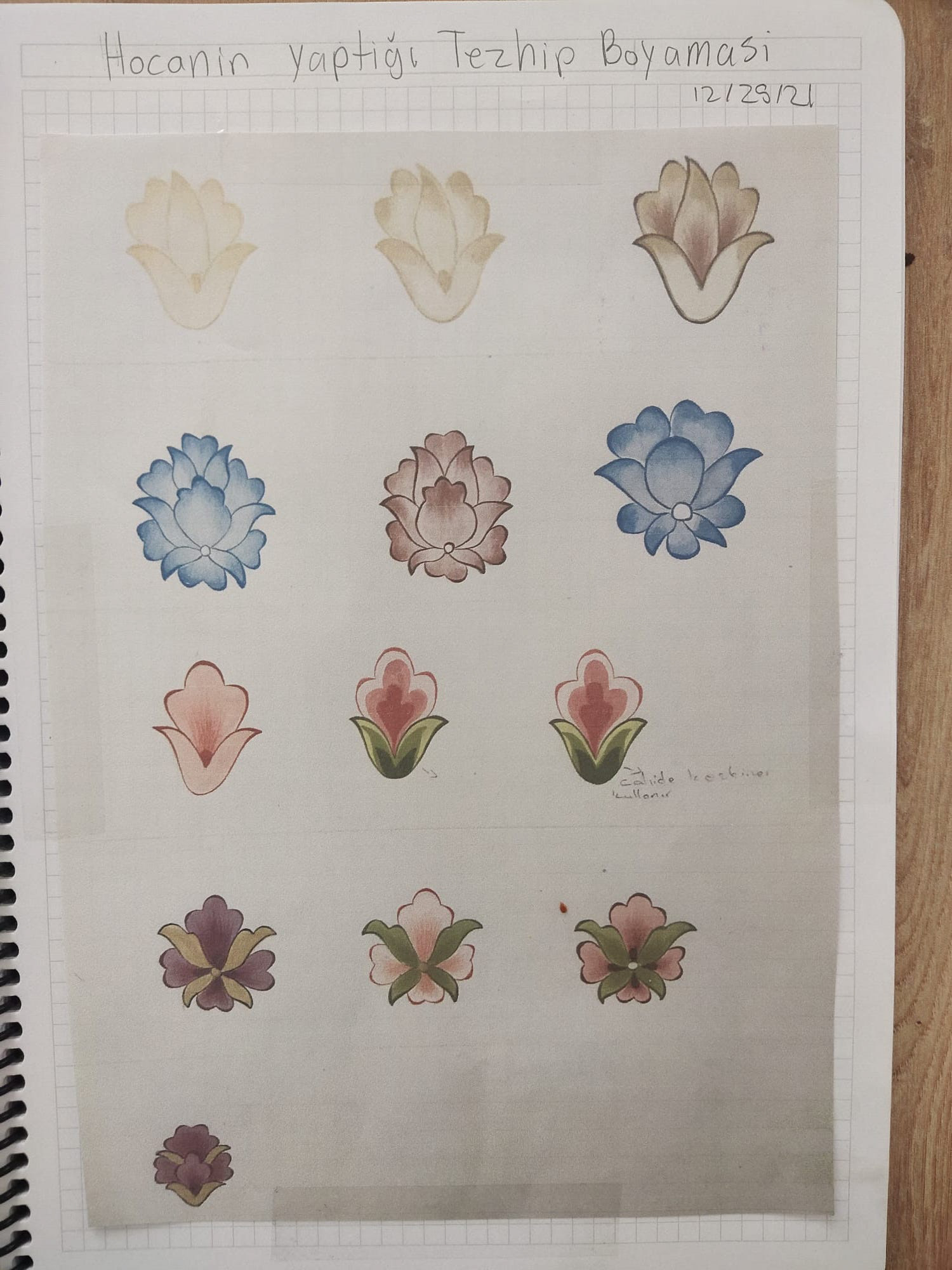

The Line THAT Breathes

Originating as an Uyghur art form in the 9th century, Illumination thrived during the eras of the Timurids, Ottomans, and Mamelukes. Tezhip is derived from the Arabic root 'zeheb' and means gilding, adorning with gold. Female artists of this art are called müzehhibe, and male artists are also called müzehhip. They created intricate designs on paper for books and sheets (illuminated panels). The 18th century witnessed new motifs, adding depth and richness to this art form. Prominent Illumination artists include Gülnur Duran, Çiçek Derman, Şahin İnalöz, Cahide Keskiner, Ülker Erke, Melek Anter, and Münevver Üçer.

In Tezhip, lines do not move in rigid directions; they flow, curve, and spiral with the grace of an S-shape. Each line is soft, continuous, uninterrupted. There are no sharp breaks, no isolated marks. Every line must return, connect, or dissolve into another. A line that leads nowhere does not belong. Not a surface design, but the geometry of being. The movement of the line reflects the rhythm of nature, where nothing ends, everything transforms. A line may begin and end on the page, but within it lives the sensation of infinity.

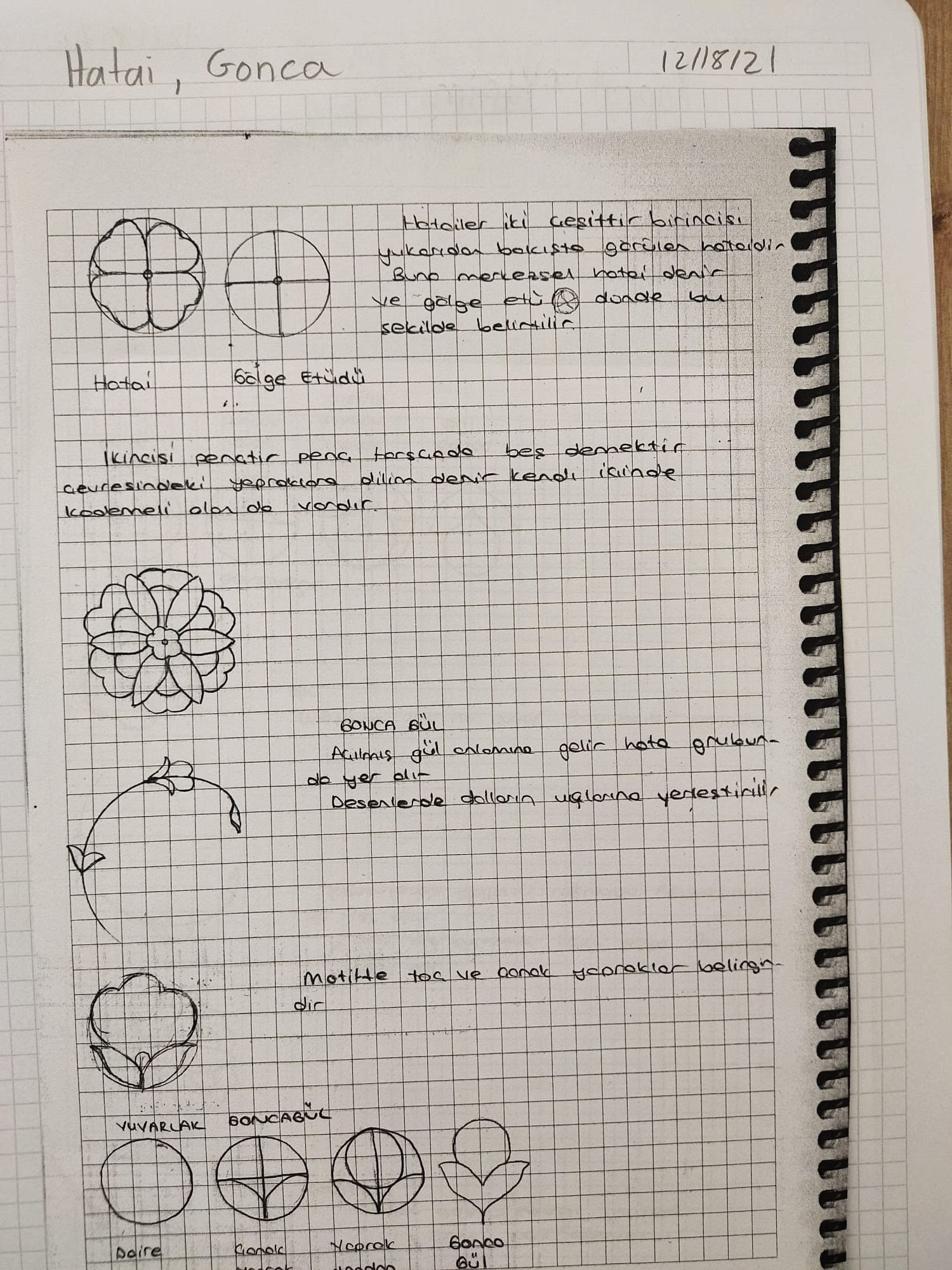

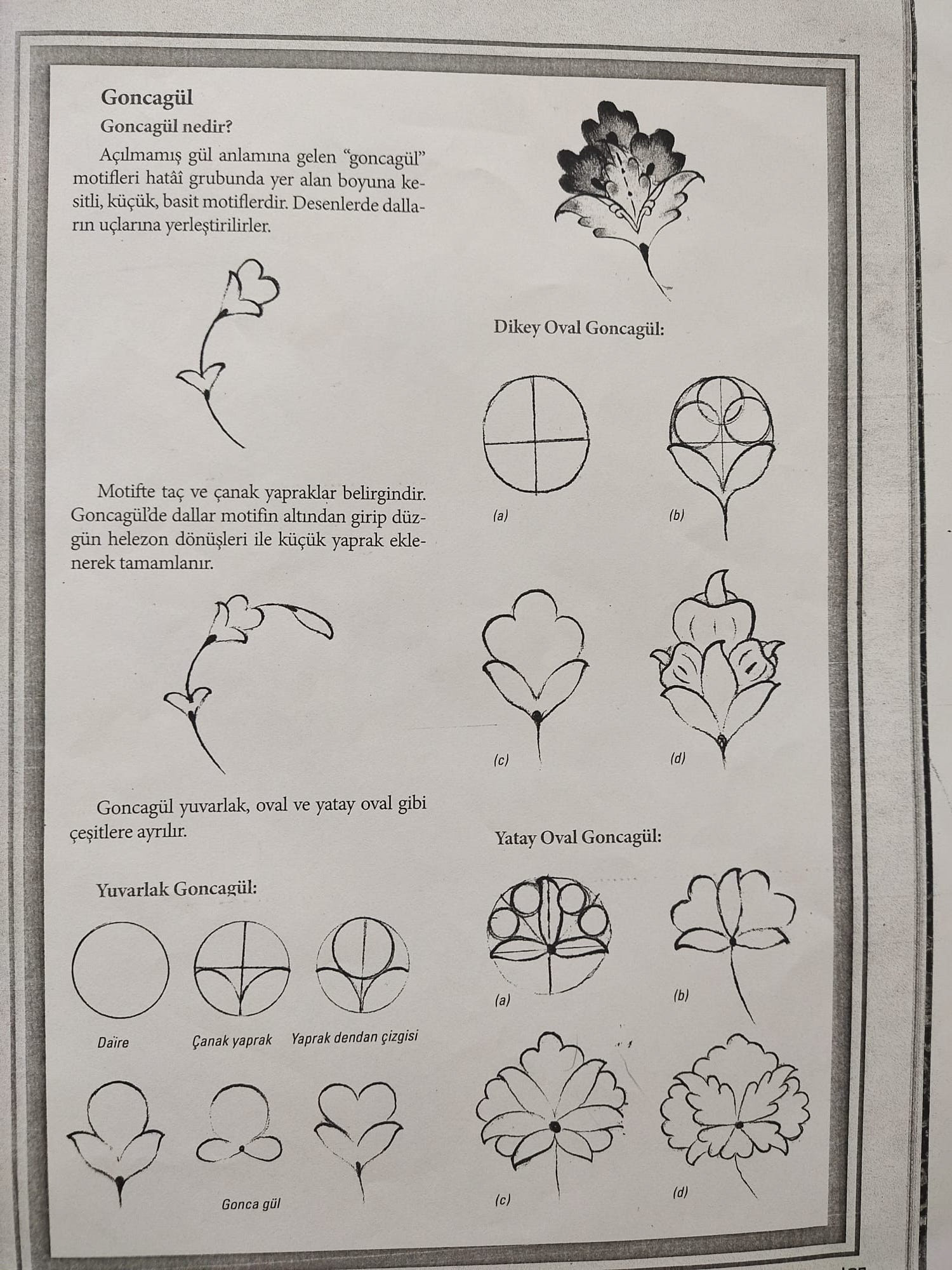

There is no randomness in Tezhip. Every motif emerges from meaning. Forms such as Rûmi, Hatai, Penç, and Saz Yolu carry symbolic weight. Rûmi speaks of spiritual unfolding and eternal return. Hatai stimulates the flowers of paradise, the unseen realms of existence. When Rûmi motifs intertwine, they reveal a deeper truth: all things are connected, and all beings reflect one another through the visual expression of vahdet, the oneness at the heart of creation.

Before the hand moves, intention is set. Niyet (intention) anchors the act. Tezhip does not begin with the eye but with the heart. Each stroke must carry energy. If the artist lacks stillness, the line falters. If the mind is unsettled, the brush will tremble. A proper line is not simply drawn; it is breathed. The hand becomes an extension of the inner state, the movement a silent invocation. Tezhip becomes a meditation, a rhythm that guides the mind to stillness and allows the soul to surface.

Lines never exist alone. Isolation breaks the integrity of the form. Every element must lead into another or return to its source. This reflects the principle of tevhid, unity in diversity. A motif that floats without connection is empty, devoid of soul.

The spiral form, seen in Rûmi and Münhanî motifs, is more than a visual element. It reflects sacred motion. It recalls the turning of the dervish, the orbit of planets, the unfolding of leaves. These curves are not forced; they arise. True symmetry in Tezhip is not mechanical but organic. It follows the proportions of nature, like the structure of a petal or the balance of a face. It is harmony that breathes. Perfection here is not sterile; it is alive, filled with subtle irregularity that reveals depth.

Each technique reflects an aspect of inner reality. Halkârî represents the diffusion of light into form, gold spreading like spiritual radiance. Zer-efşan, the scattering of gold, appears spontaneous but is guided by intention. Münhanî curves trace the inner self's undulations. Şükûfe captures the slow unfolding of the spirit, a quiet blooming shaped by patience. Aher is not just a preparation layer; it is the hidden body of the painting, the base that holds the soul of the pigment. Tahrir, the outlining of form, is an act of awareness. It defines without restriction, sets a boundary without breaking flow.

Tezhip is a visible prayer. Gold is not an embellishment; it is a symbol of truth. It radiates from the center, measured, purposeful, never excessive. Rhythm gives the lines breath. Silence, the untouched space between forms, is not emptiness but presence. Blank areas are not absent; they are where the soul rests.

If the line does not lead you back to your essence, it should not be drawn. Tezhip demands more than precision; it asks for presence. It is not a question of what you draw, but why you draw it. The foundation is always the same: symbol, intention, flow, balance, and silence. That is where Tezhip begins. That is where it returns.

How to Become a Muzehhip or Muzehhibe

In the Ottoman era, becoming an illumination artist was a demanding yet prestigious path, rooted in both spiritual devotion and artistic mastery. Tezhip, the art of illumination, required years of apprenticeship and strict guidance under a master.

illuminators underwent years of disciplined apprenticeship, mastering classical motifs and techniques under a mentor before earning a diploma to practice and teach professionally.

1. Initiation as a Student (Talebe): Aspiring students, often from artisan families, began young by studying basic drawing, brushwork, and motifs. They sought mentorship in palace workshops, such as Nakışhane-i Hümayun, or in private ateliers, where they usually trained under female or open-minded male masters. Entry often required proof of dedication and skill.

2. Training Under a Master: Traveling 5–10 years, training focused on tracing classical 15th–16th century models, mastering motifs like rumi, hatayi, and tulips, learning gold preparation, composition, and symbolic color use. Students also handled chores, reinforcing humility and discipline.

3. Practice and Progress: Students began with murakkaa (practice albums), moved to borders, then full-page works, all closely reviewed by the master. Repetition, patience, and inner stillness were key, as tezhip was as much a meditative act as a visual one.

4. Receiving the İcazetname: Once the student produced a refined original piece, the master granted an icazetname; a diploma of mastery; allowing her to sign works, accept commissions, and teach.

5. Professional Life: Certified illuminators worked in court ateliers, especially under rulers like Süleyman the Magnificent, or took private commissions. While signatures were rare due to the culture of humility, some gained fame through elite patronage and collaboration with other artists.

Habibti (My Beloved) in Bloom #5

In this work, I centered the Arabic word "حبيبتي" (Habibti)—my beloved—as both anchor and offering. The calligraphy is set in a vertical medallion inspired by classical manuscripts, against a gold ground enclosed in an olive green frame with white floral motifs, evoking gentleness and devotion. A black ornamental finial extends the form above and below, rooting it in tradition.

To the right, a bouquet of white flowers blooms in a style inspired by Shukufe method and miniature painting, softened by personal expression. I painted white roses and cosmos with golden-yellow centers, surrounded by chamomile-like blossoms for texture and a sense of humility. Green stems and leaves are tied with a golden ribbon, forming a gesture of offering.

A gold-leaf border with intricate arabesque frames the composition, flourishes in each corner, echoing the traditions of illuminated manuscripts. Gold ink and leaf are used throughout to illuminate the ribbon, the medallion, the border, carrying a quiet thread of light across the piece.

Note on Language: Habibi vs Habibti

Habibi (حبيبي) means “my beloved” when speaking to a man; Habibti (حبيبتي) is the feminine form, used when addressing a woman. Both are expressions of deep affection in Arabic, used for loved ones, family, and close friends.

DIGITAL DRAFTs

TRADITIONAL PROCESS

FINAL WORK of habibti in bloom

EXHIBITION 2024

PRESENTING:

TULIP SHUKUFE MAJESTIC ALIF

ROSE SHUKUFE

MAGNIFICENT FRESCO

Heavenly Dream of Levni

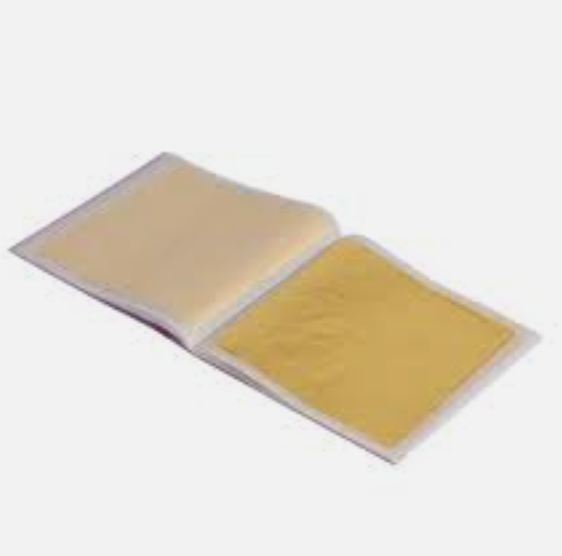

USE OF GOLD IN TEZHIP

Did you know that real gold is used in Tezhip Illumination Art?

In the Art of Tezhip Illumination, gold leaf is used to decorate intricate designs. This age-old tradition has been practiced for centuries and adds a touch of symbolic significance, visual impact, durability, contrast, and artistic versatility.

In illumination art, gold is prized for its symbolic richness and visual impact. Its reflective qualities enhance artwork aesthetics and contrast sharply with other colors, highlighting key elements. Gold's durability ensures preservation, and its versatility in forms like leaf or paint allows for varied artistic expressions.

Key aspects of gold's use in illumination

Symbolic Significance: Gold is used in illumination art to symbolize wealth, power, enlightenment, and divinity.

Visual Impact: Gold's radiance and reflective properties enhance the visual appeal of illuminated manuscripts and artworks.

Durability: Gold is resistant to corrosion and fading, ensuring the long-lasting preservation of gilded elements in illuminated works.

Contrast: Gold contrasts sharply against other colors and materials, emphasizing important elements in the artwork.

5️⃣Artistic Versatility: Gold can be applied in different forms, such as gold leaf or paint, and various techniques can enhance its visual effects.

Tezhip Exhibition - 2023

Anisa's two pieces were showcased at the Aydın Classical Handicrafts Illumination (Tezhip) Exhibition, which took place in 2023 at the Cihanoglu Complex. Elif Aydin, Anisa's teacher, guides her in her work.

TULIP SHUKUFE #1

"Shukufe" is a transliteration of the Persian word شکوفه, which means "blossom." In botanical symbolism, flowers often symbolize beauty, growth, and renewal. Tulips are a popular and significant flower in many cultures, particularly Persian and Ottoman. In Persian literature, the tulip is often associated with love and passion. In the Ottoman Empire, the tulip symbolizes perfection and beauty. "Tulip Shukufe" refers to an illuminated design featuring a blossoming tulip, aligning with the practices of Tezhip, where the natural beauty of flowers is often represented in an abstract and stylized manner.

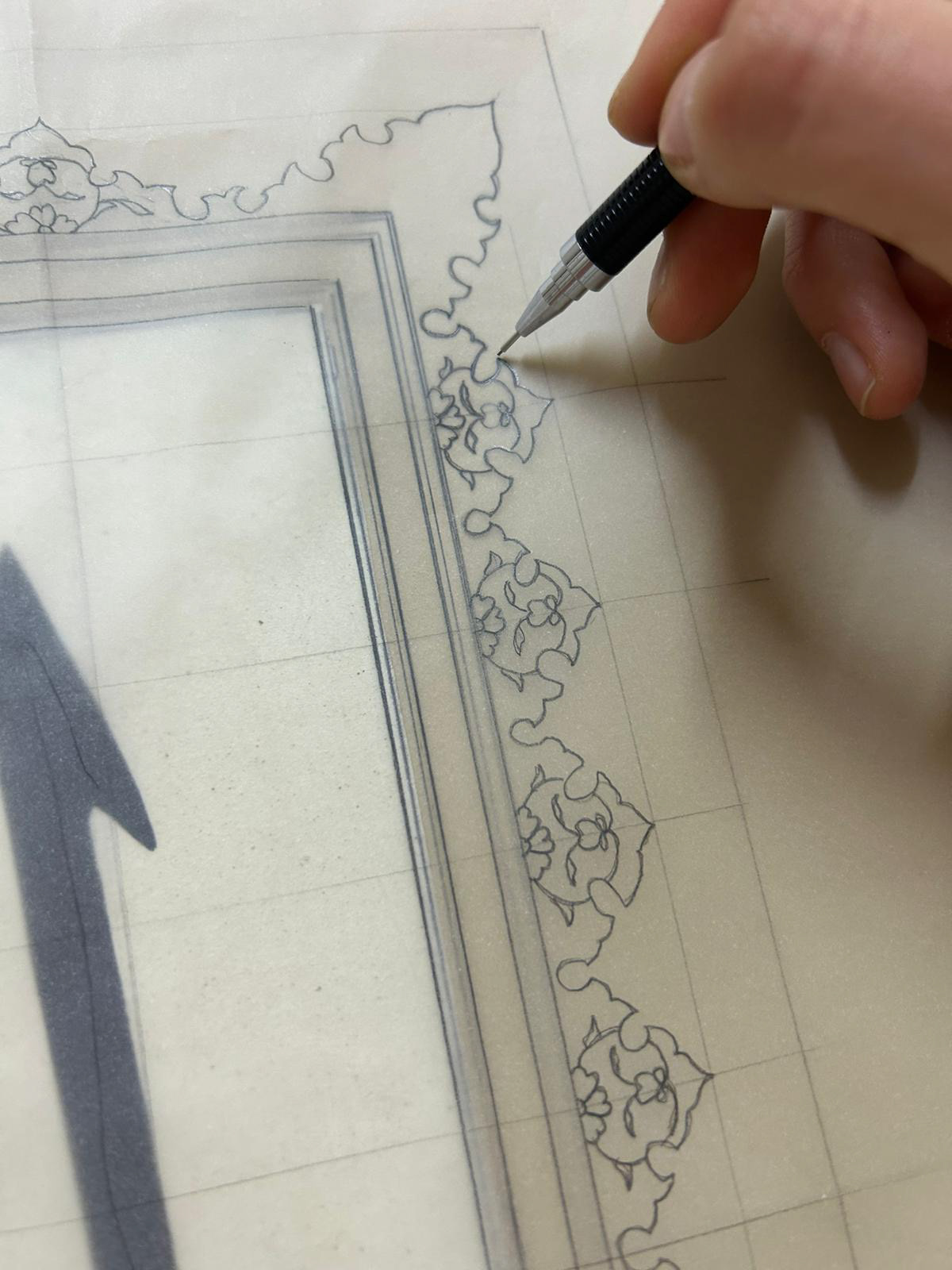

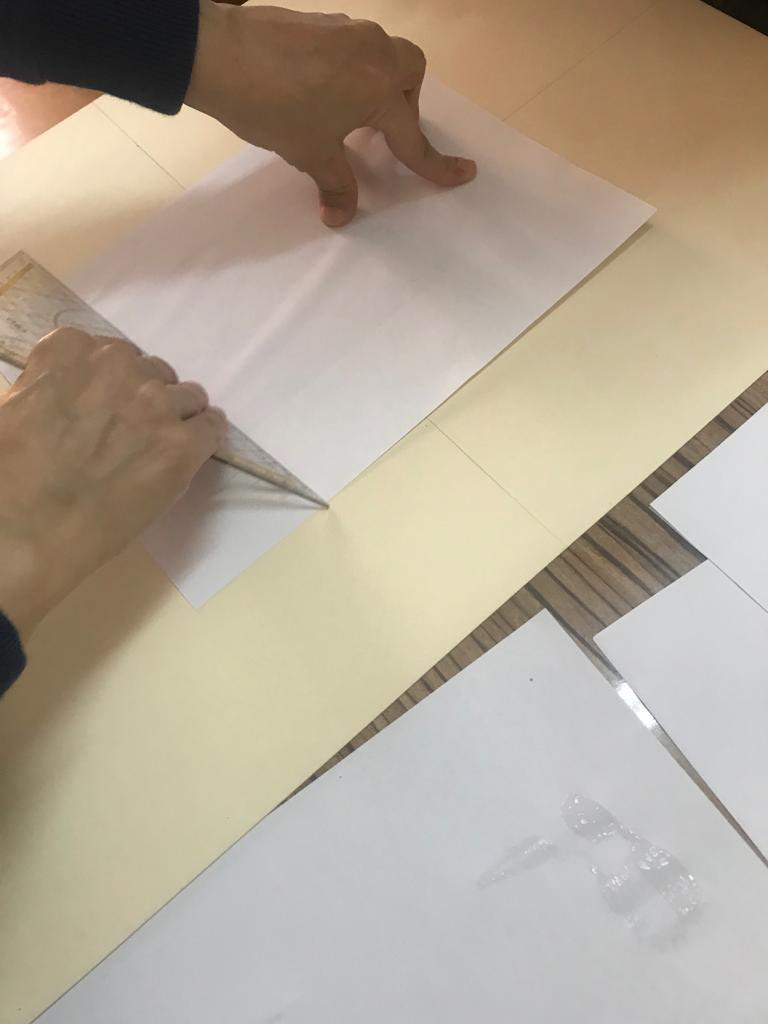

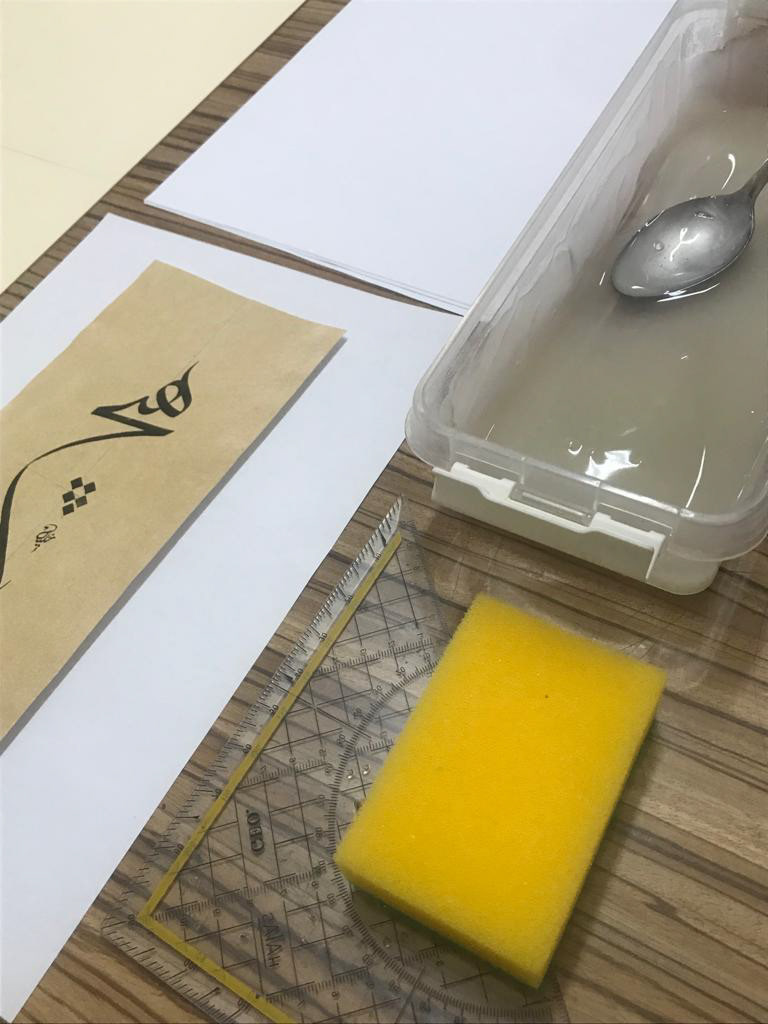

PROCESS OF "TULIP SHUKUFE"

VARIOUS BACKGROUNDS

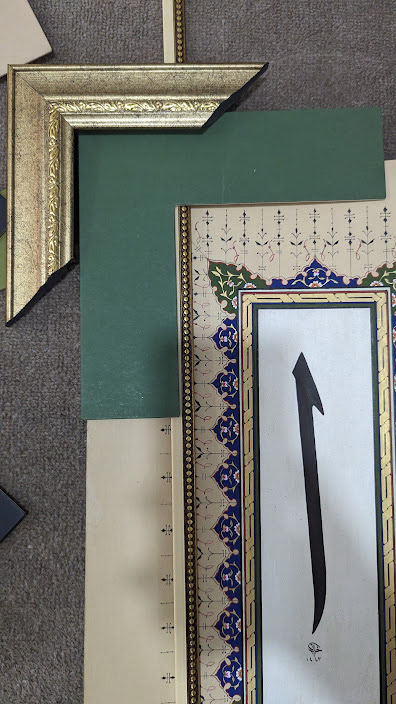

FRAMING PROCESS of "TULIP SHUKUFE"

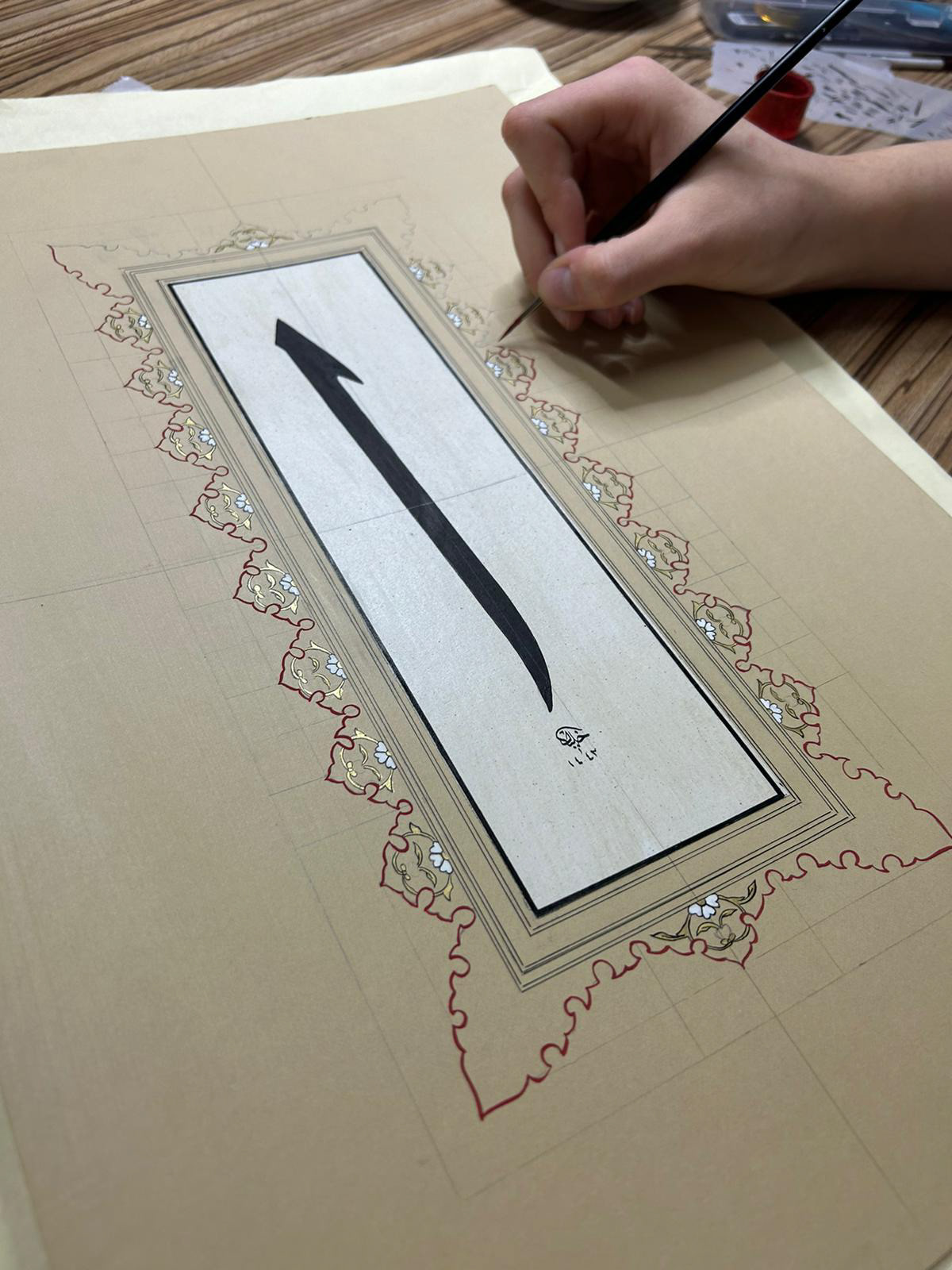

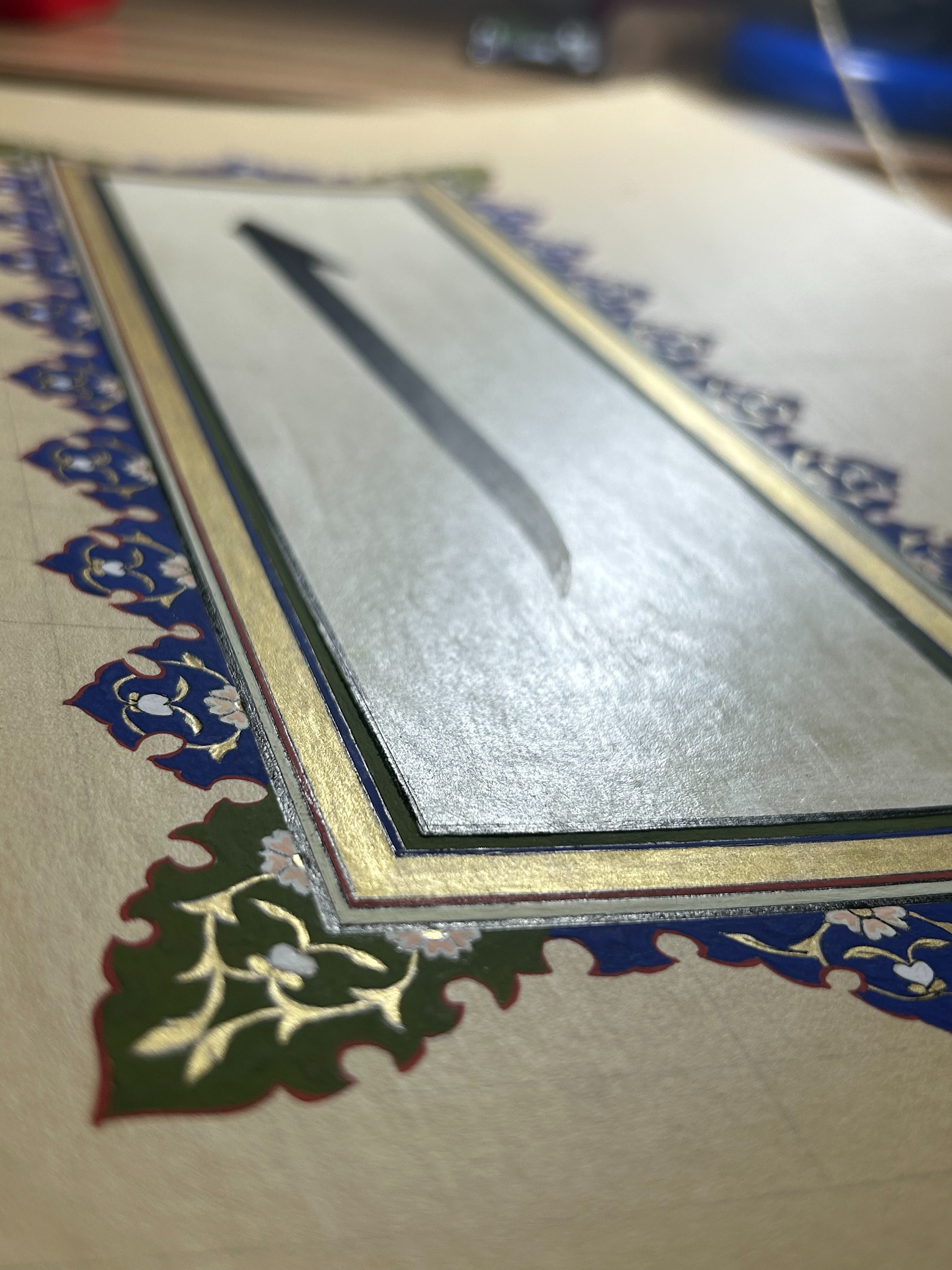

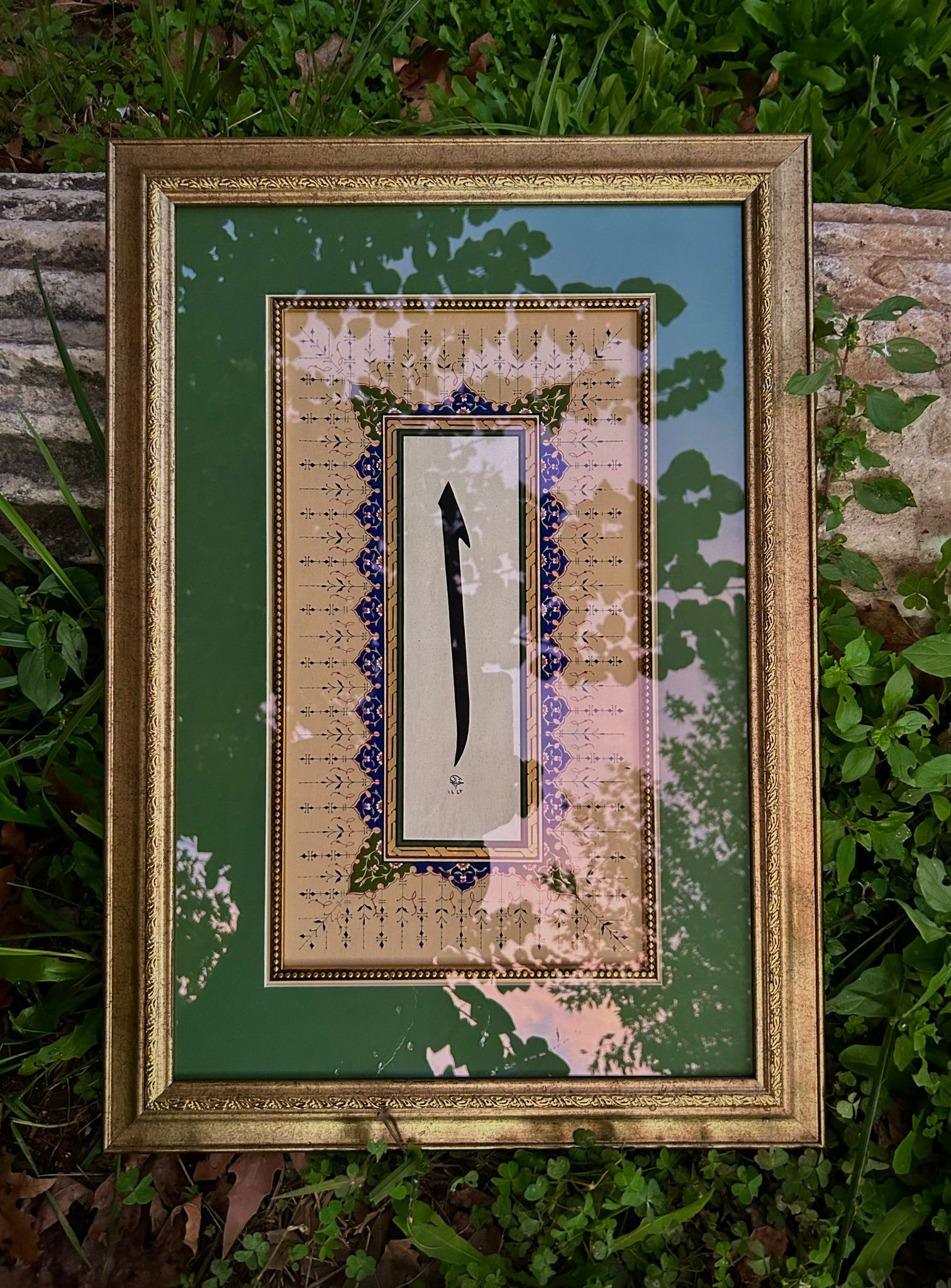

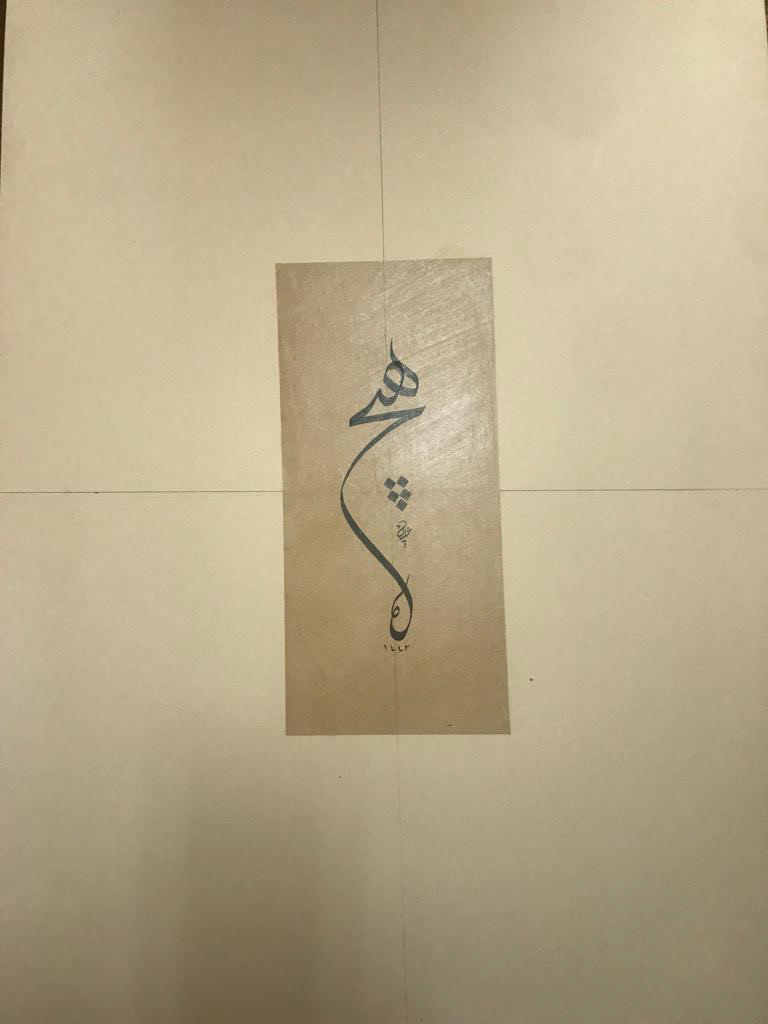

MAJESTIC ALIF #2

Alif's Isolated Form is ا. Letter name (Classical pronunciation) is Alif. Letter name in Arabic script أَلِف. Alif, signifying the first letter 'A' in the Arabic alphabet, bears profound symbolic and spiritual significance often linked to unity and singularity. The concept underscores recognizing the divine through the human form, mirroring the belief that humans are fashioned in God's image and carry a spark of the divine essence. This imbues humans with the potential for spiritual ascension and the quest for unity with the divine. The elongated vertical line of ALIF, reminiscent of an upright human figure, represents the pursuit of spiritual enlightenment. Its stylized shape beautifully encapsulates the connection between heaven and earth, serving as a symbolic conduit linking the tangible and spiritual domains.

PROCESS oF MAJESTIC ALIF

FRAMED: MAJESTIC ALIF

ROSE SHUKUFE #3

Shukufe is an artistic technique that employs flower motifs to create breathtakingly beautiful works of art. It refers to the unopened flowers and buds that inspire intricate designs. The rose, known for its delicate petals and intoxicating fragrance, is revered among poets and artists as the ultimate symbol of love and beauty. This regal flower is sometimes called the "sultan of flowers," a title that speaks to its majestic presence.

Creating shukufe art can be a lengthy process, requiring the gradual accumulation of color layers through continuous, meticulous brushwork. This technique, known as shading, results in a gradual gradient of color that adds depth and dimension to the work. While it may be a slow and tedious process, the result is a seamless and stunning work of art that is well worth the effort. Whether incorporated into a painting, a piece of poetry, or a decorative piece of art, shukufe and its evocative flower motifs will surely add a touch of sophistication and elegance to any piece.

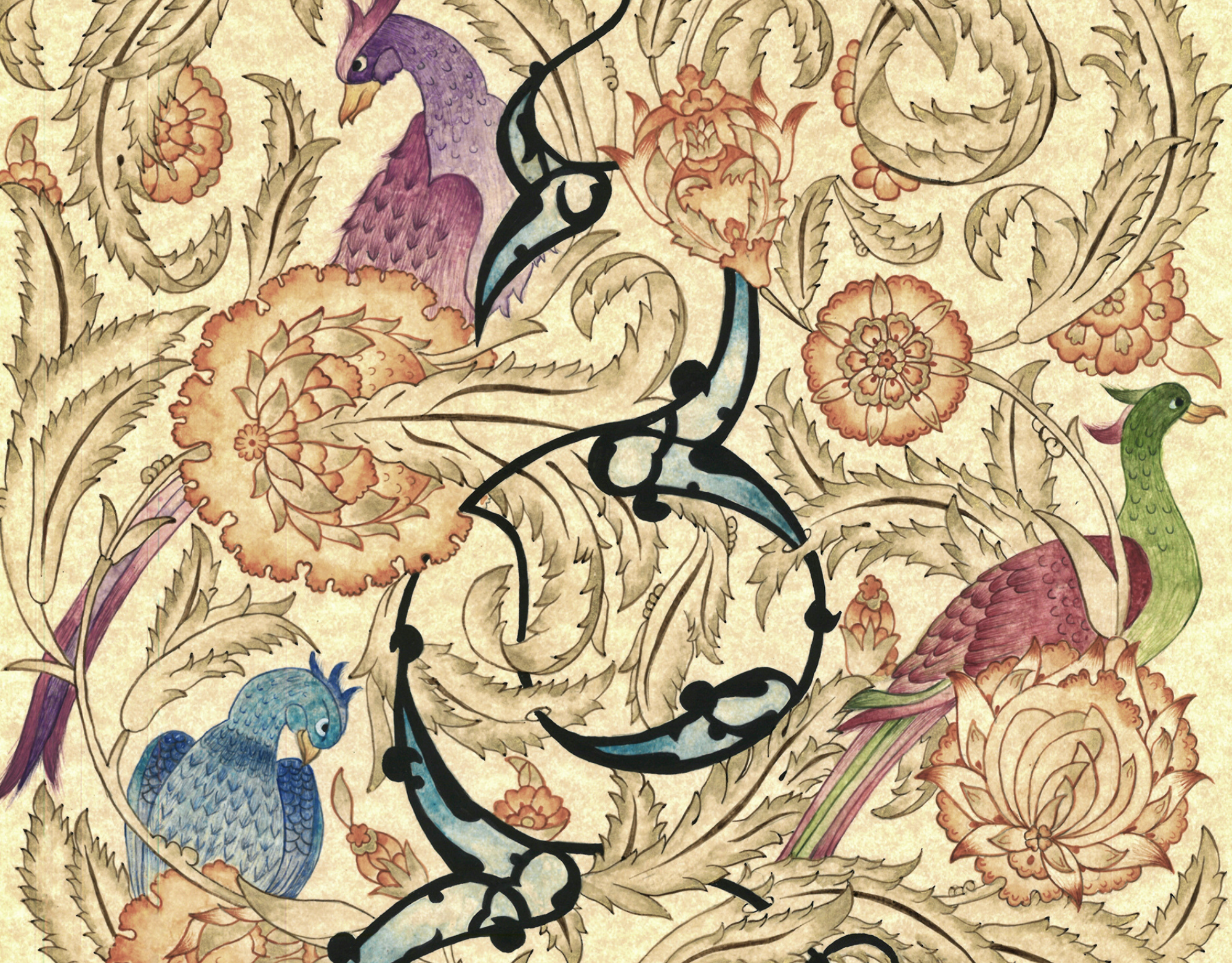

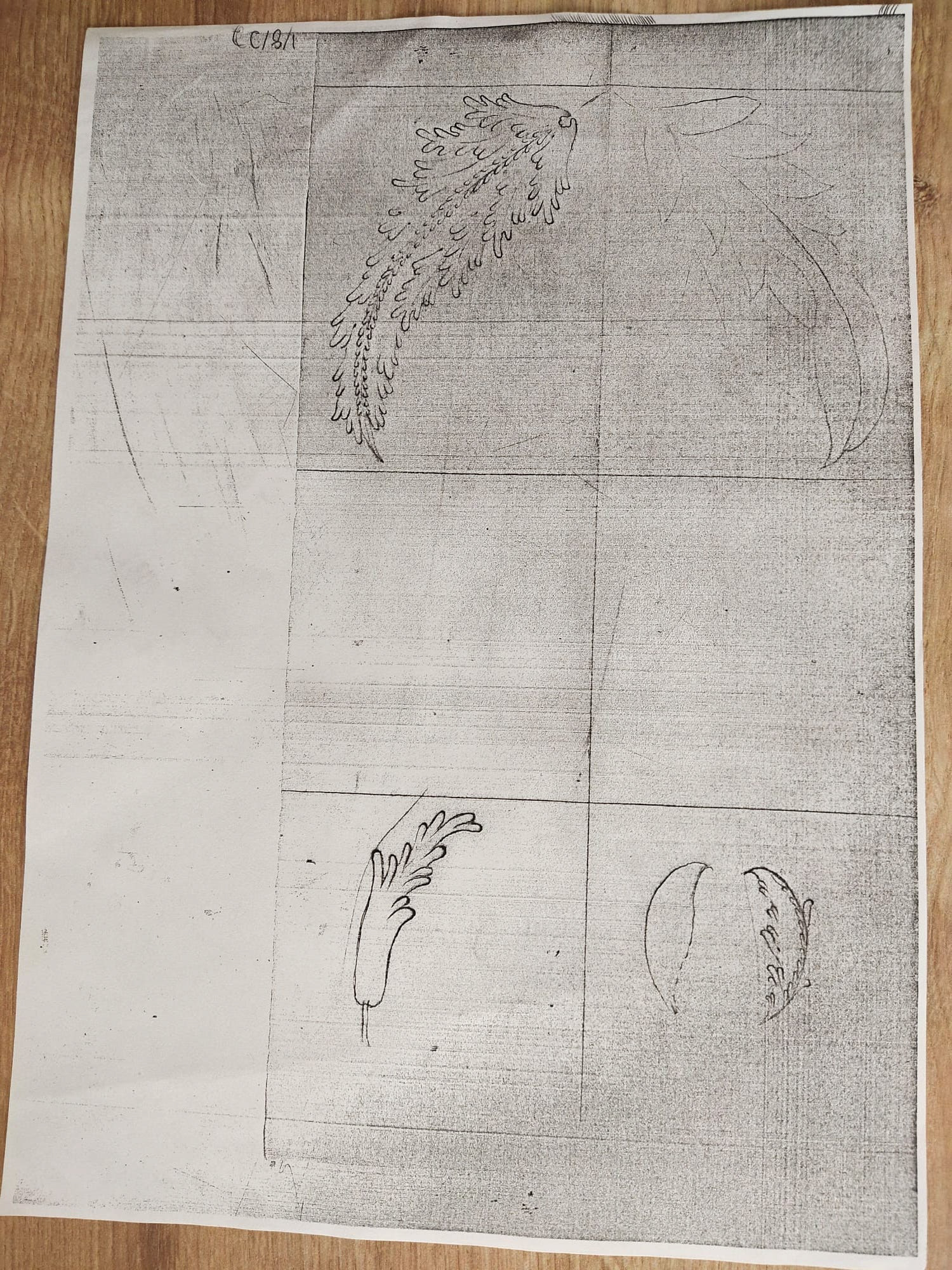

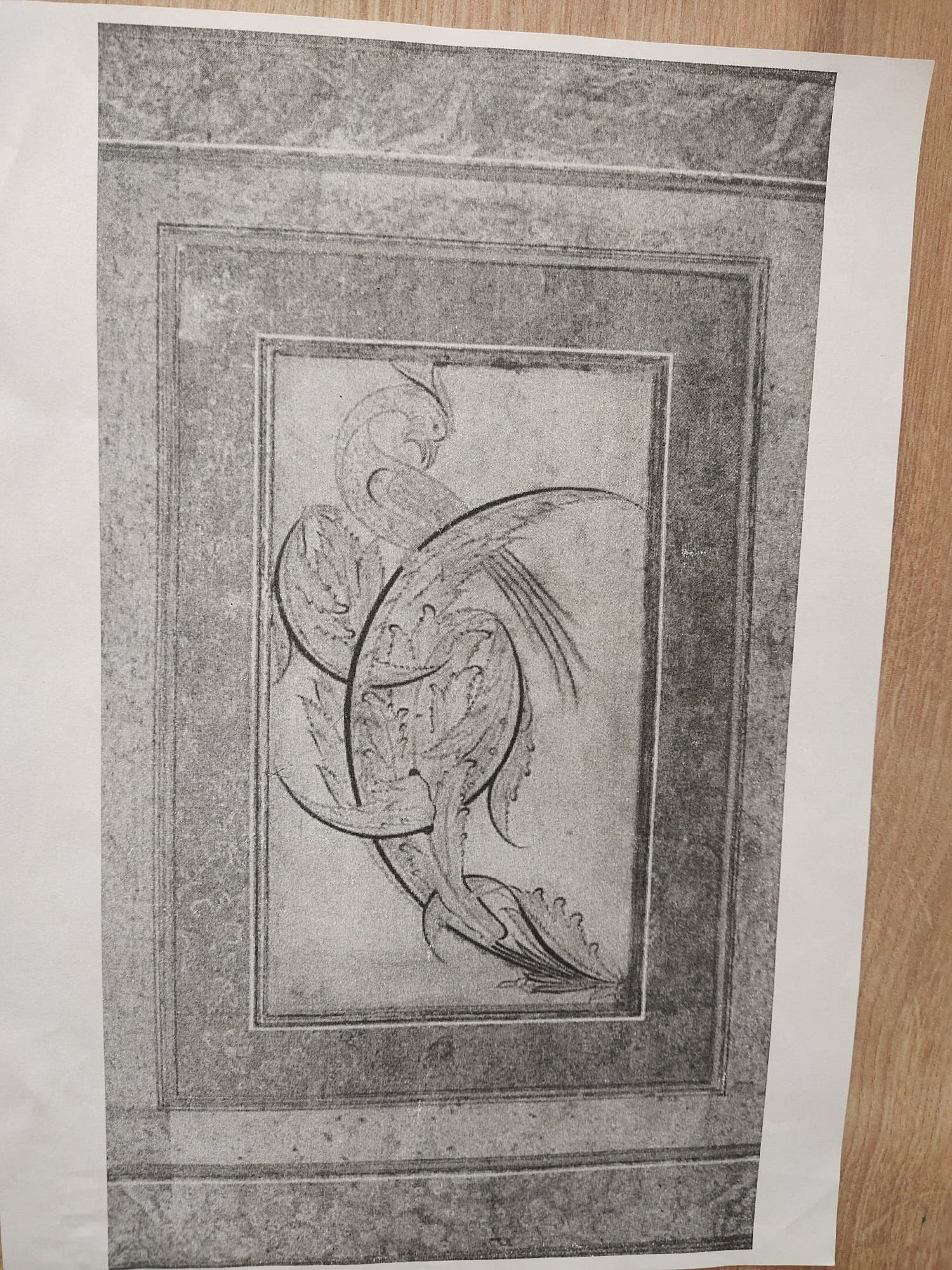

MAGNIFICENT FRESCO #4

"Magnificent Fresco" is a masterful integration of Tezhip, the traditional Islamic art of illumination using real gold, with classic wallpaper motifs reimagined for contemporary interior design. This artwork blends intricate, symbolic floral and fauna motifs, including elegant representations of pheasants, symbolic of beauty and nobility, with the sophistication of Rumi calligraphy, adding depth and a sacred dimension. The use of genuine gold leaf in the design pays homage to the luxurious illuminated manuscripts of the past, infusing the piece with a timeless quality. Encased in a modern double-glass frame, this work celebrates cultural legacy. It creates a seamless visual continuity between the art and the space it adorns, exemplifying a unique synthesis of historical artistry with modern design sensibilities. Process and more details can be seen here.

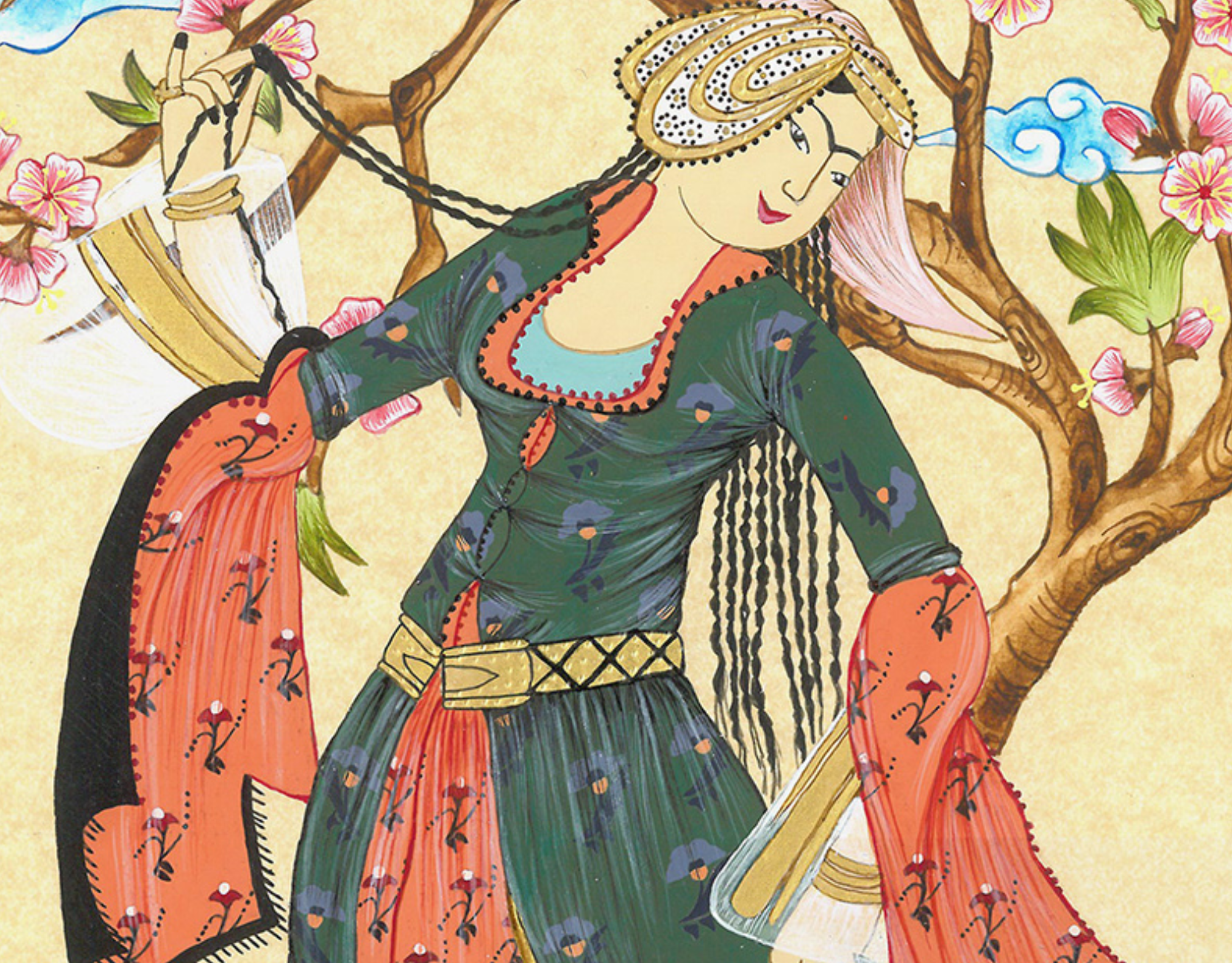

Heavenly Dream of Levni #4

"The Heavenly Dream of Levni" is a project that honors women's empowerment during the Ottoman Tulip Era, a time known for its cultural outreach and the elite's fascination with tulips. The artwork is inspired by Levni, the Tulip Era's celebrated master of miniature and realistic painting, specifically recreating his piece "Women in Attire." Enhancements include a spring-themed backdrop with pink blossoms and a "Munhani" style border featuring curvilinear motifs.

Observations of the Ottoman Era at Topkapi Palace ➡️ anisaozalp.com/istanbul

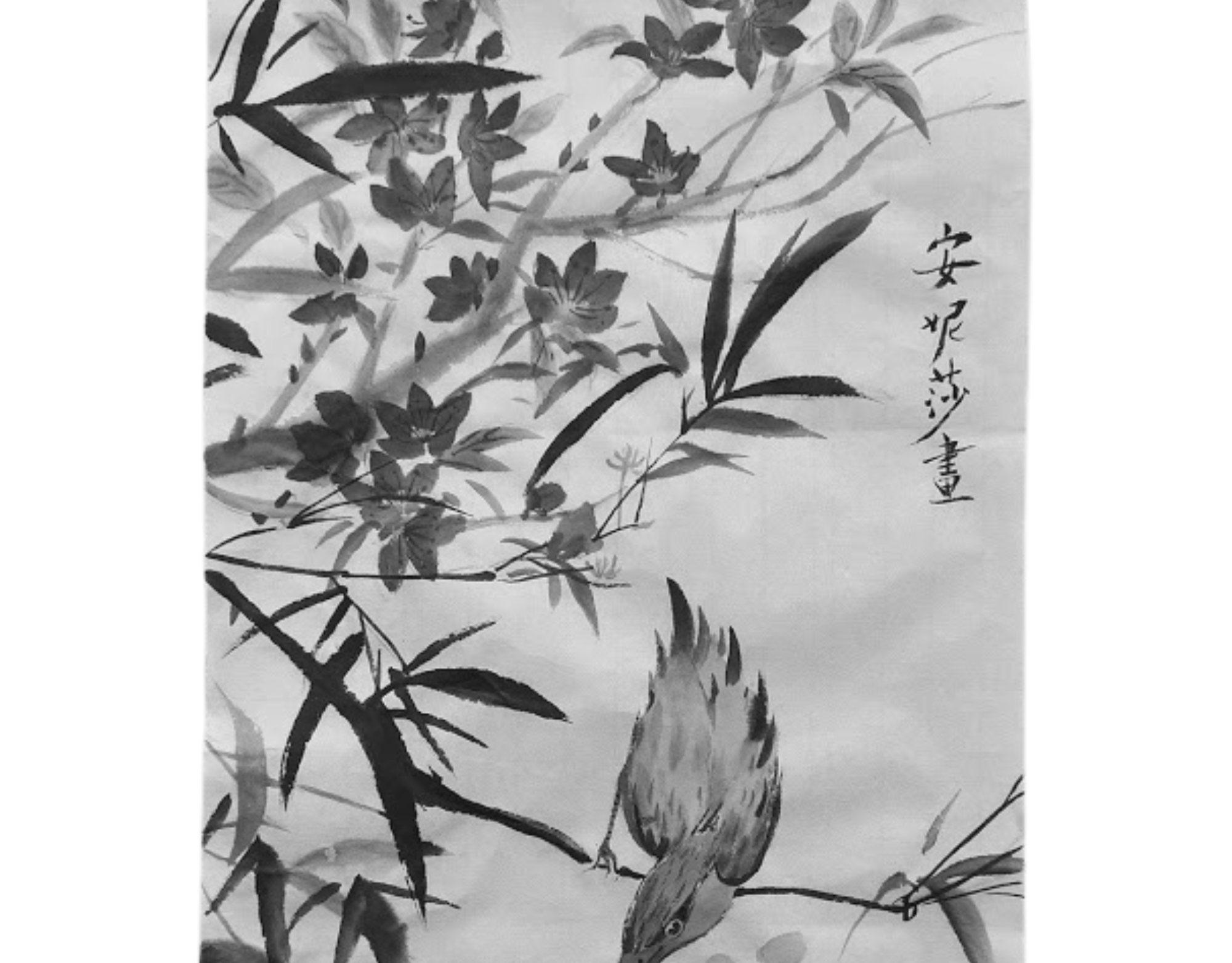

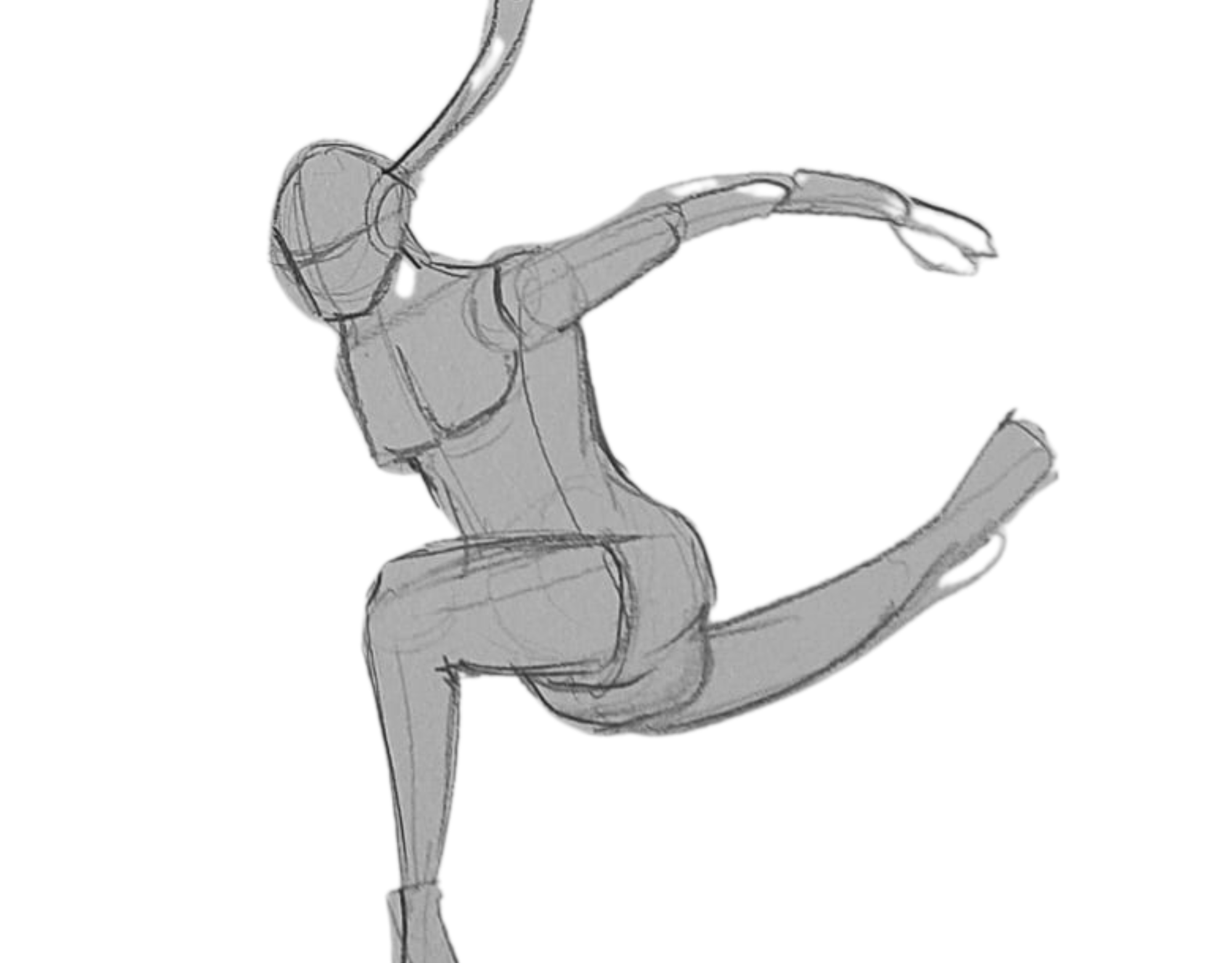

DIGITAL

SKETCH

OF

HEAVENLY

DREAM OF

LEVNI

This digital sketch reimagines Tezhip techniques, centering on "Levni's Woman," a stylized figure dressed in Ottoman-era garments. The figure is depicted in a modest pose, looking downward, with her attire intricately patterned and layered, accentuating her form with long, flowing sleeves typical of the time. The background features pink blossoms, symbolizing spring and renewal, adding a natural contrast to the historical dress. The borders are in Munhani style, featuring vibrant and traditional motifs that reflect the manuscript-like quality of Ottoman art. The artwork references the Tulip Era, a flourishing period in the 18th-century Ottoman Empire known for its cultural vibrancy. "Levni's Women" are portrayed uniquely, with visible, engaging features and clothing that enhances their femininity, setting them apart from traditional Miniature Art.

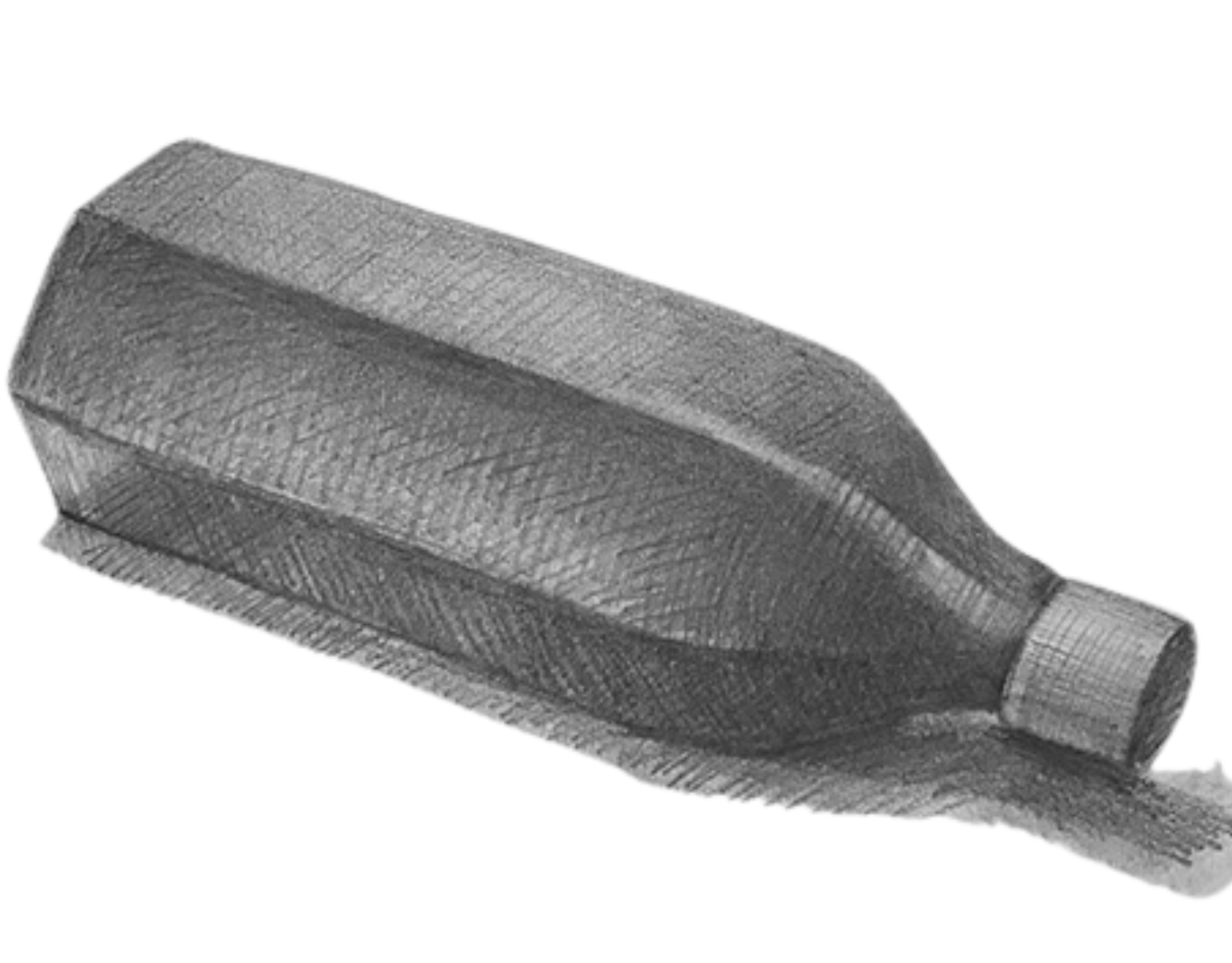

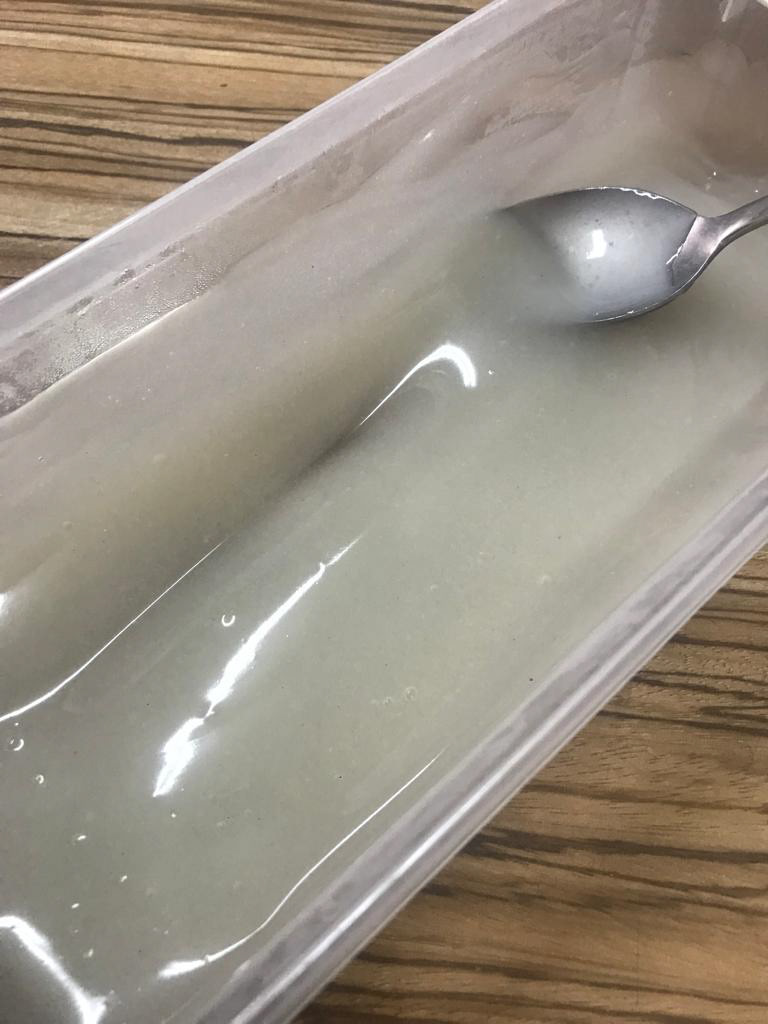

NATURAL AHER GLUE-MAKING PROCESS

What is Aher Glue? Aher glue is a traditional Ottoman adhesive made from water, starch, gelatin, and alum, used in manuscript illumination to protect paper, ease paint cleanup, and repel insects. To make natural aher glue that is suitable for use in artwork, you will need the following ingredients: ❃ 1 teaspoon of water, ❃ 2 teaspoons of starch, ❃ Half a teaspoon of gelatin, ❃ 1 quantity of alum.

STEPS ① Combine the water, starch, gelatin, and alum in a pot. ② Cook the mixture until it reaches a custard-like consistency. ③ Once cooked, the glue does not deteriorate when placed on raw cardboard and helps keep insects away. ④ When working with artwork, use this glue as it makes it easy to clean the paint.

Tezhip natural glue making

Tezhip natural glue making

Tezhip natural glue making

Tezhip natural glue making

Tezhip natural glue making

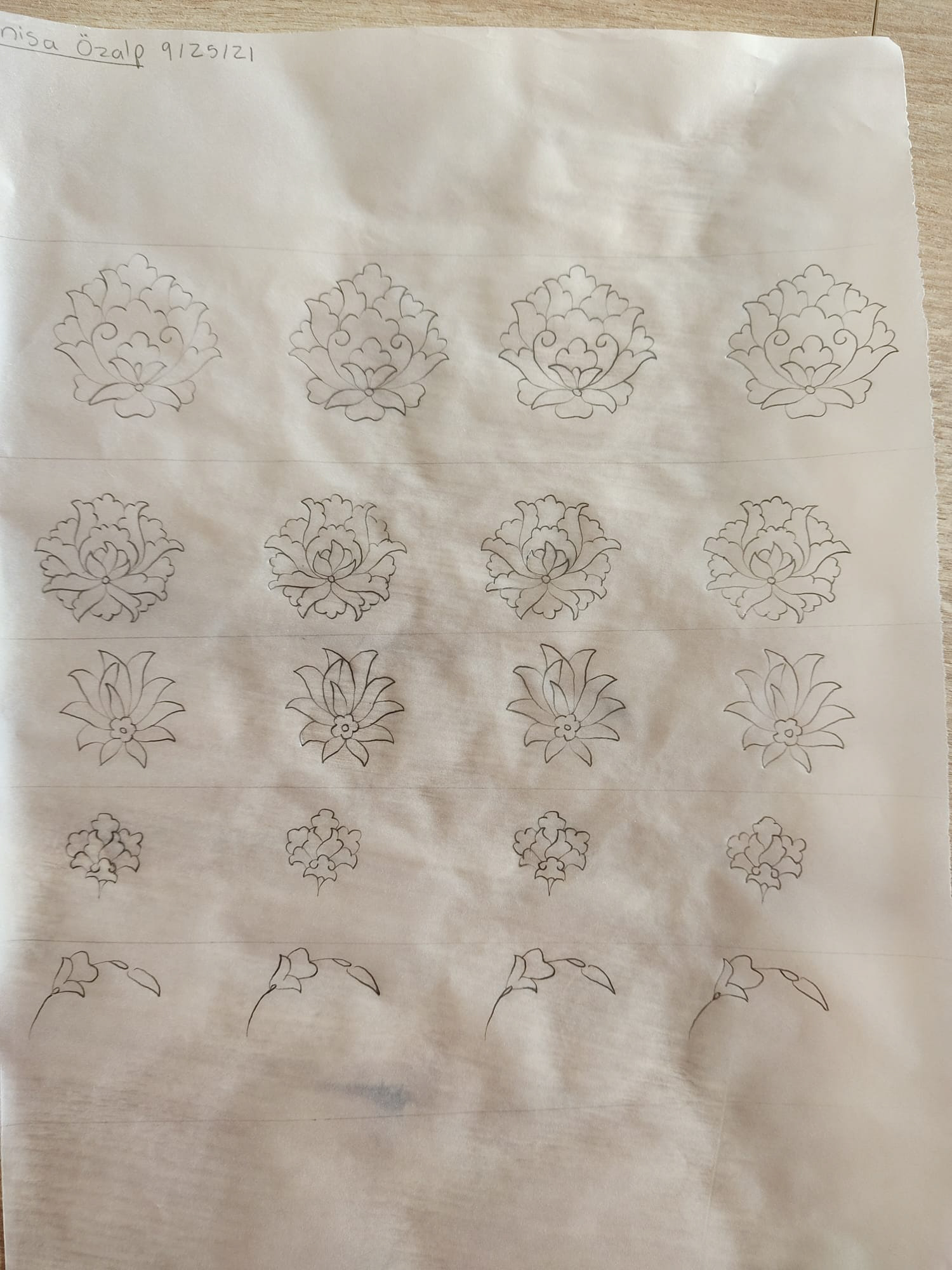

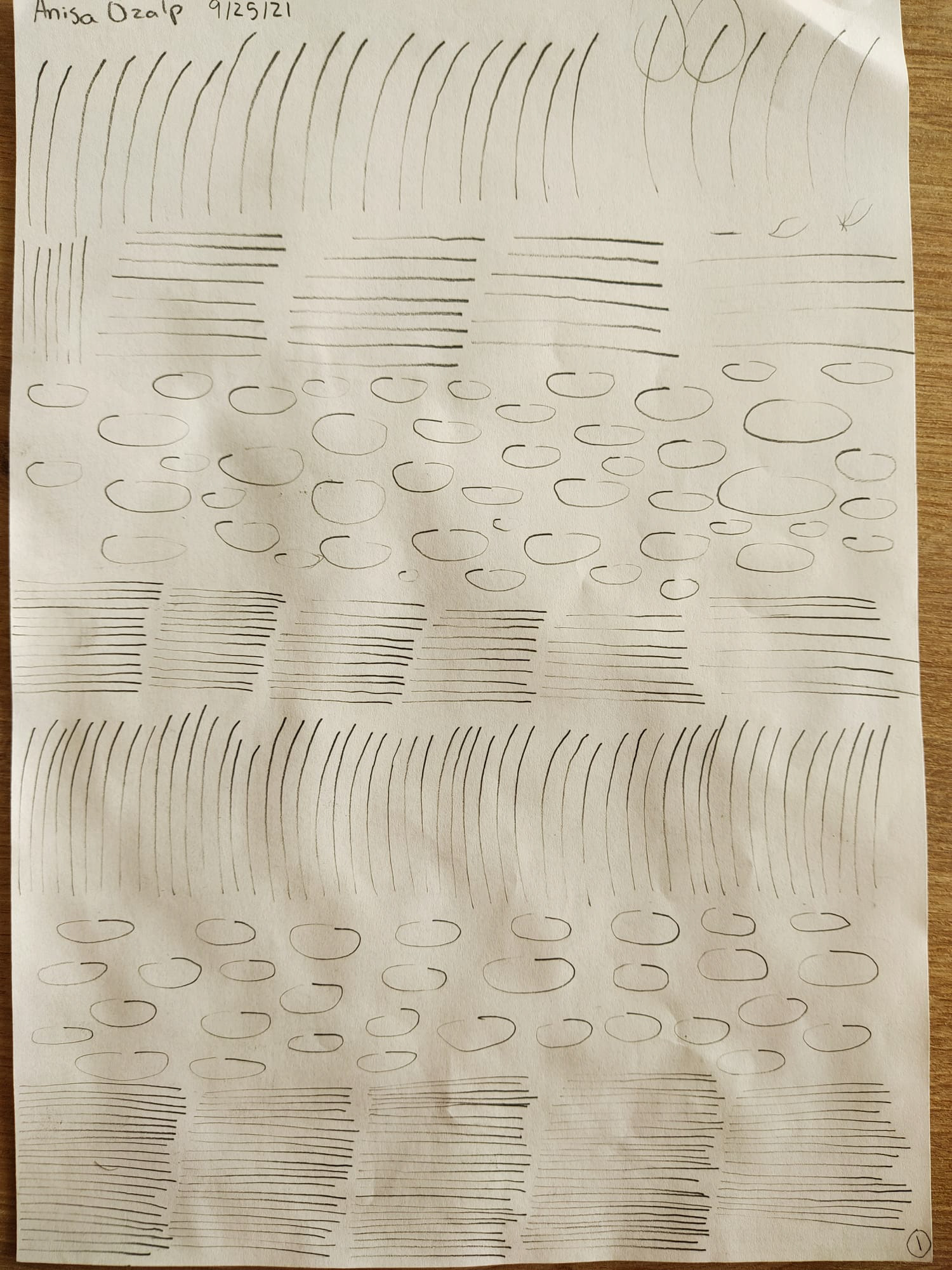

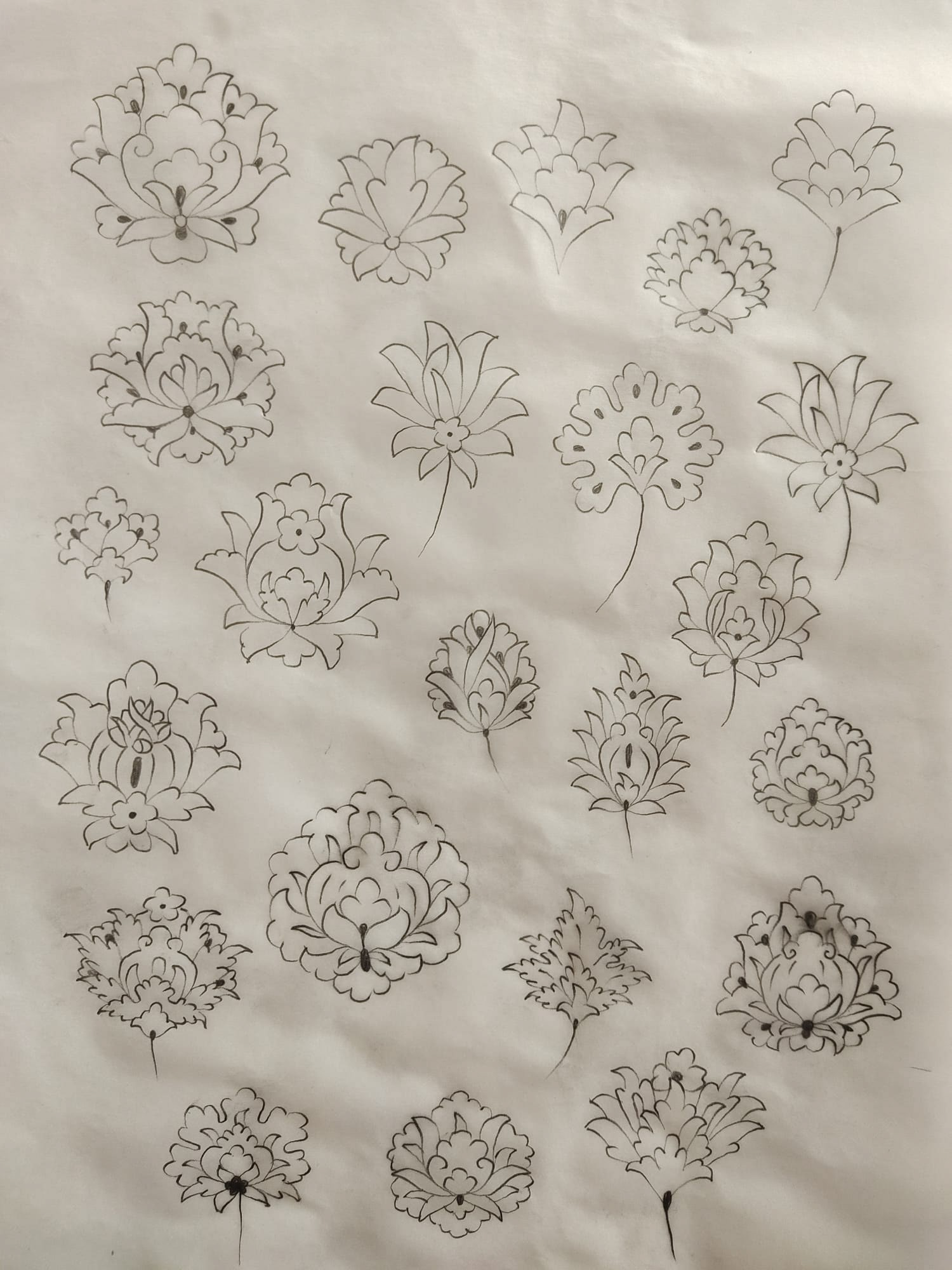

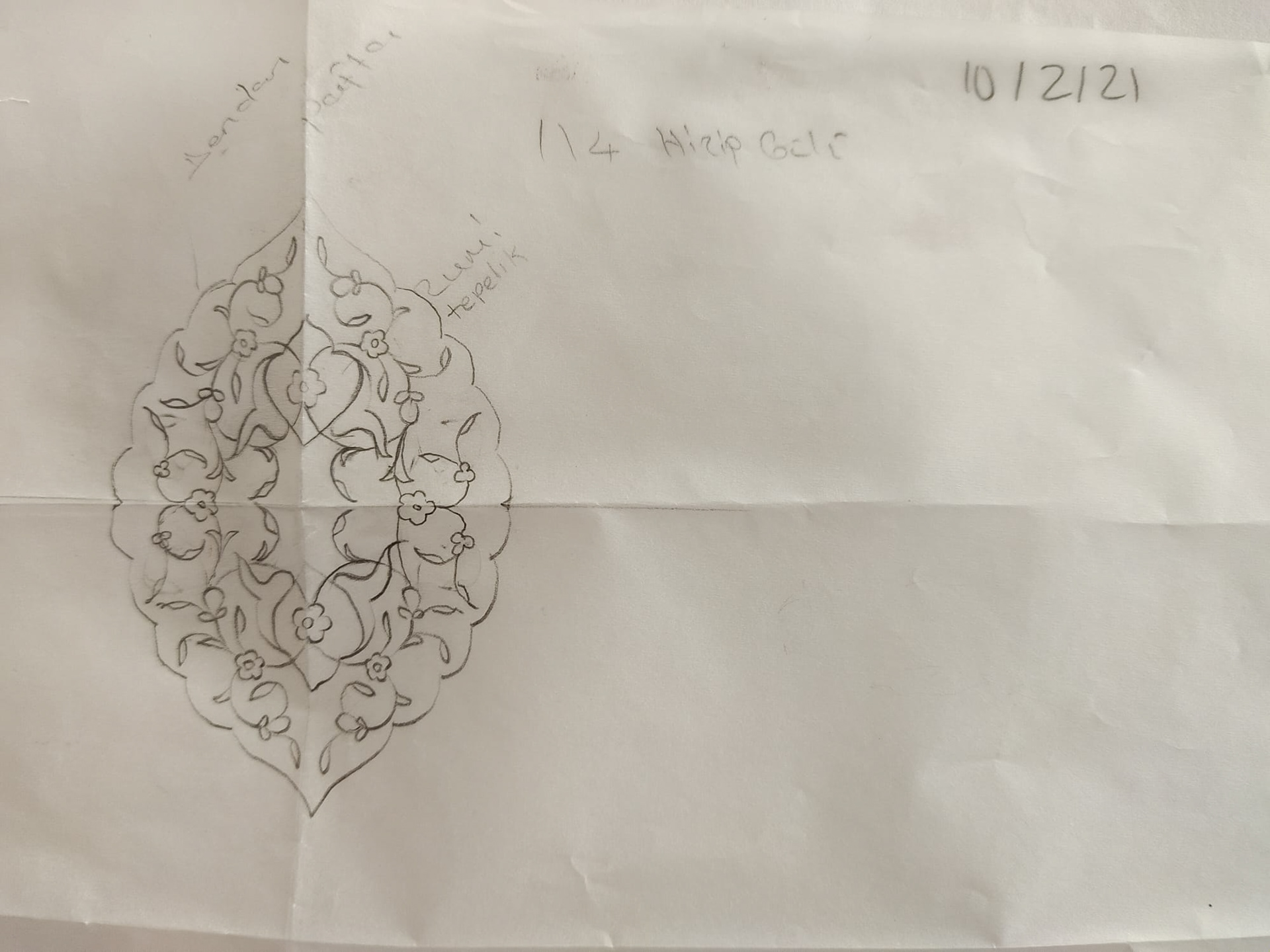

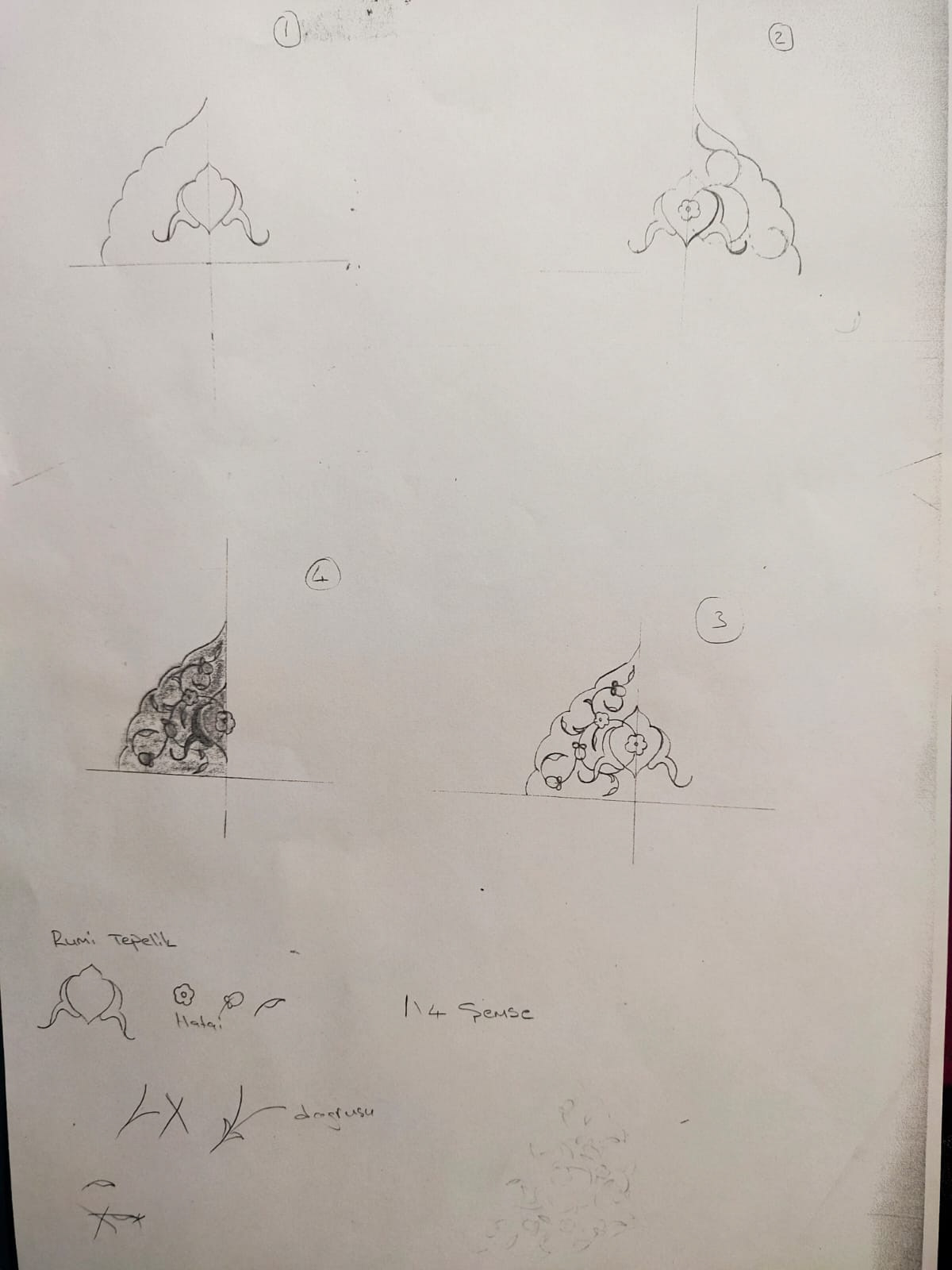

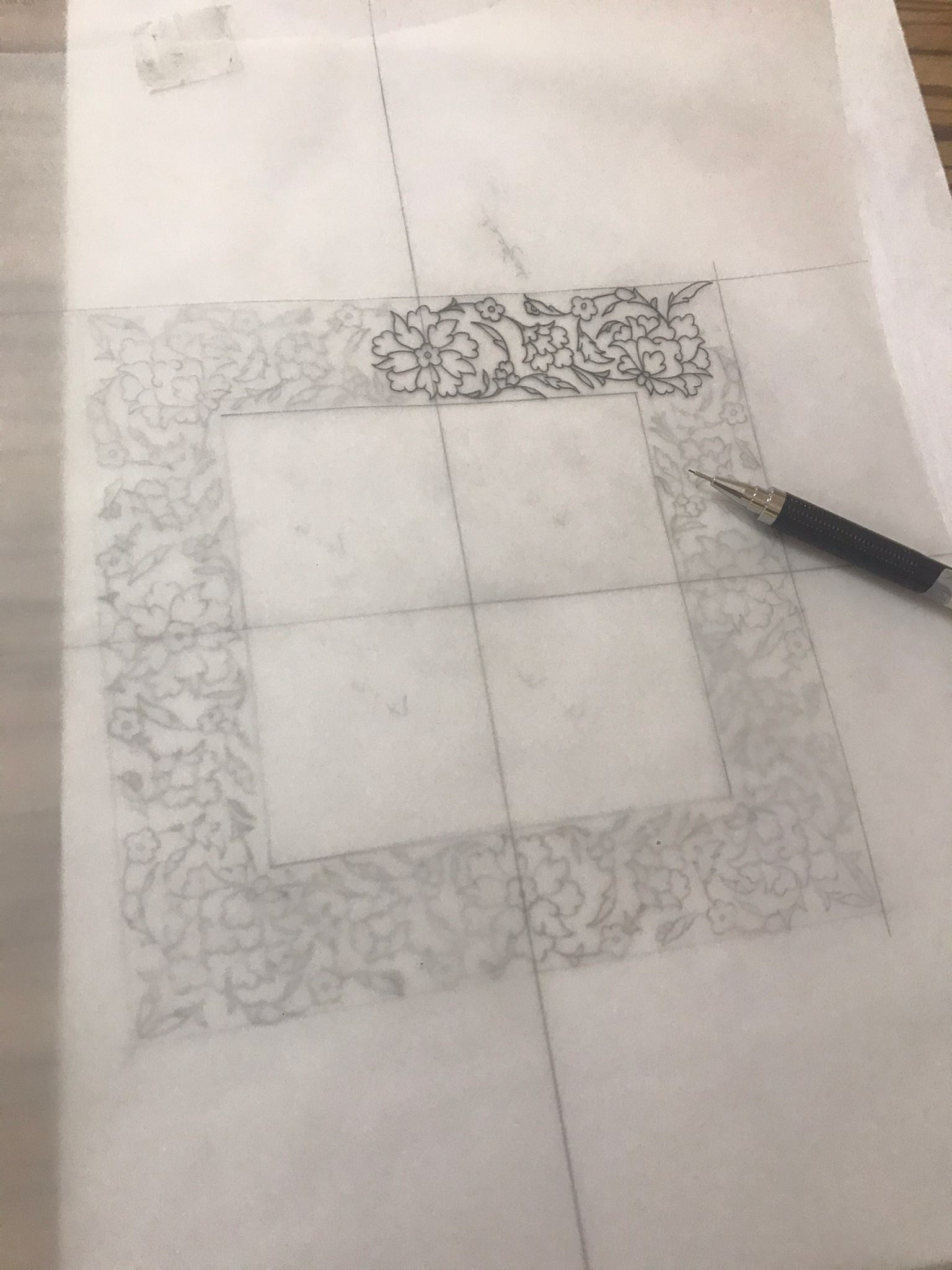

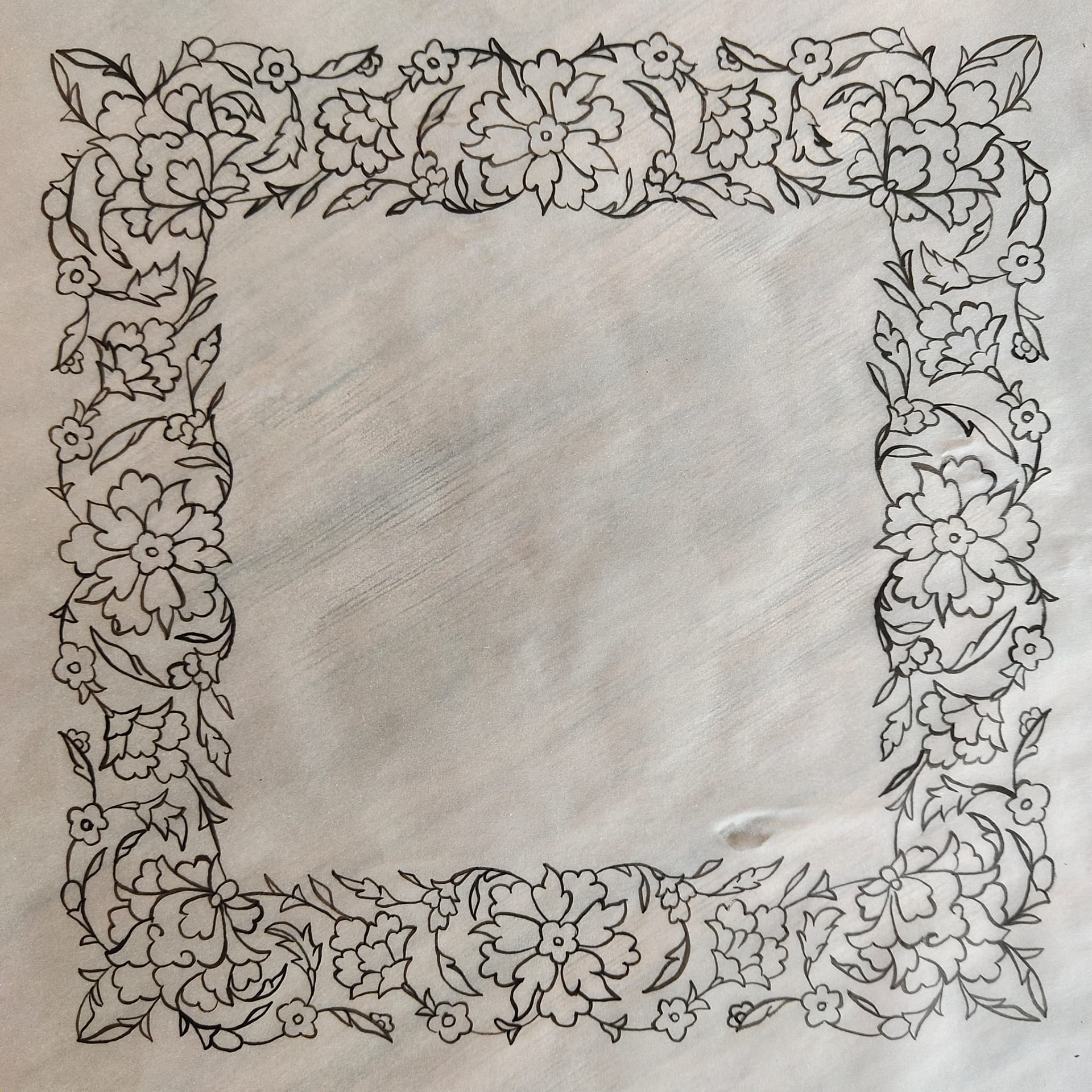

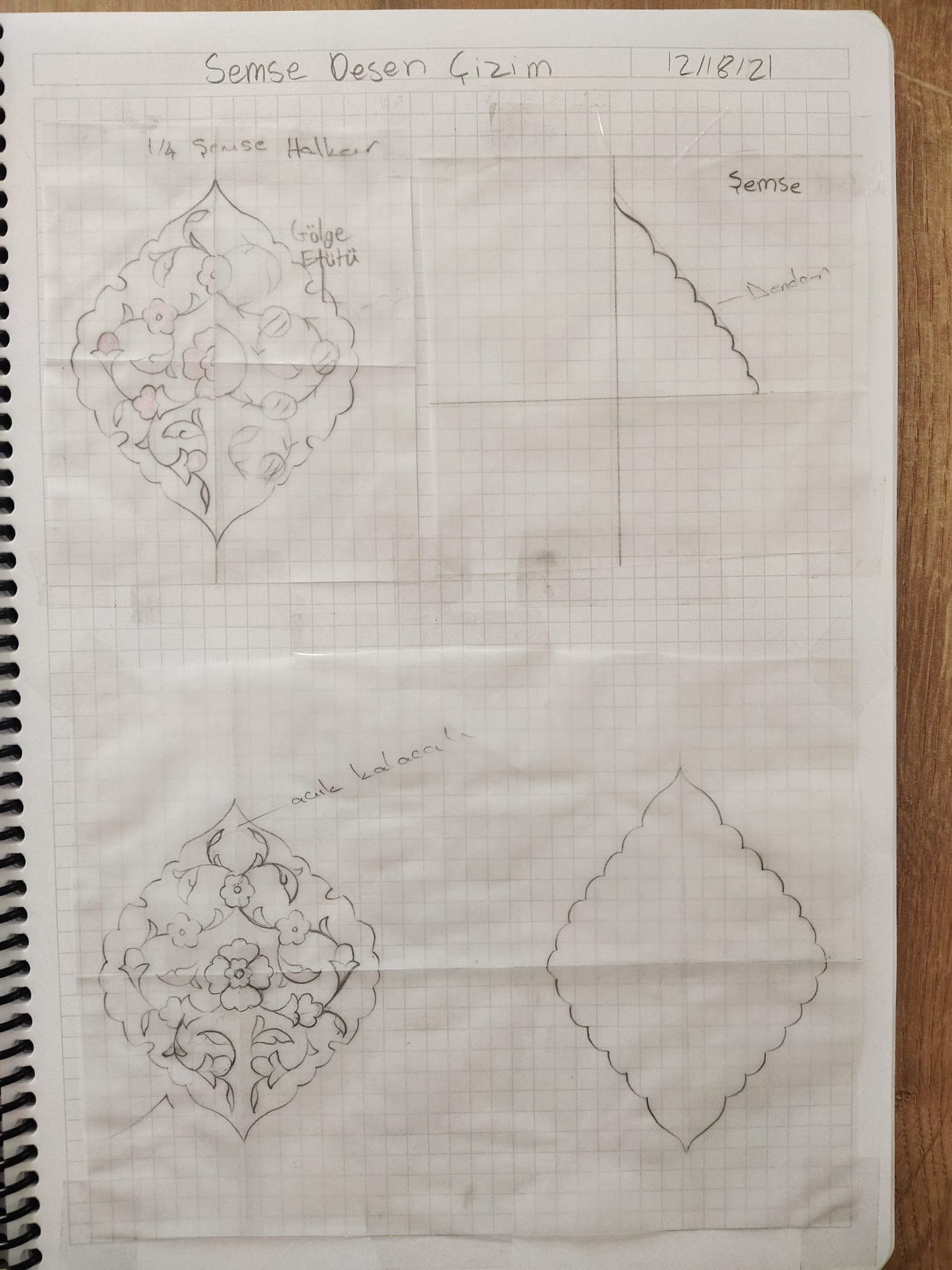

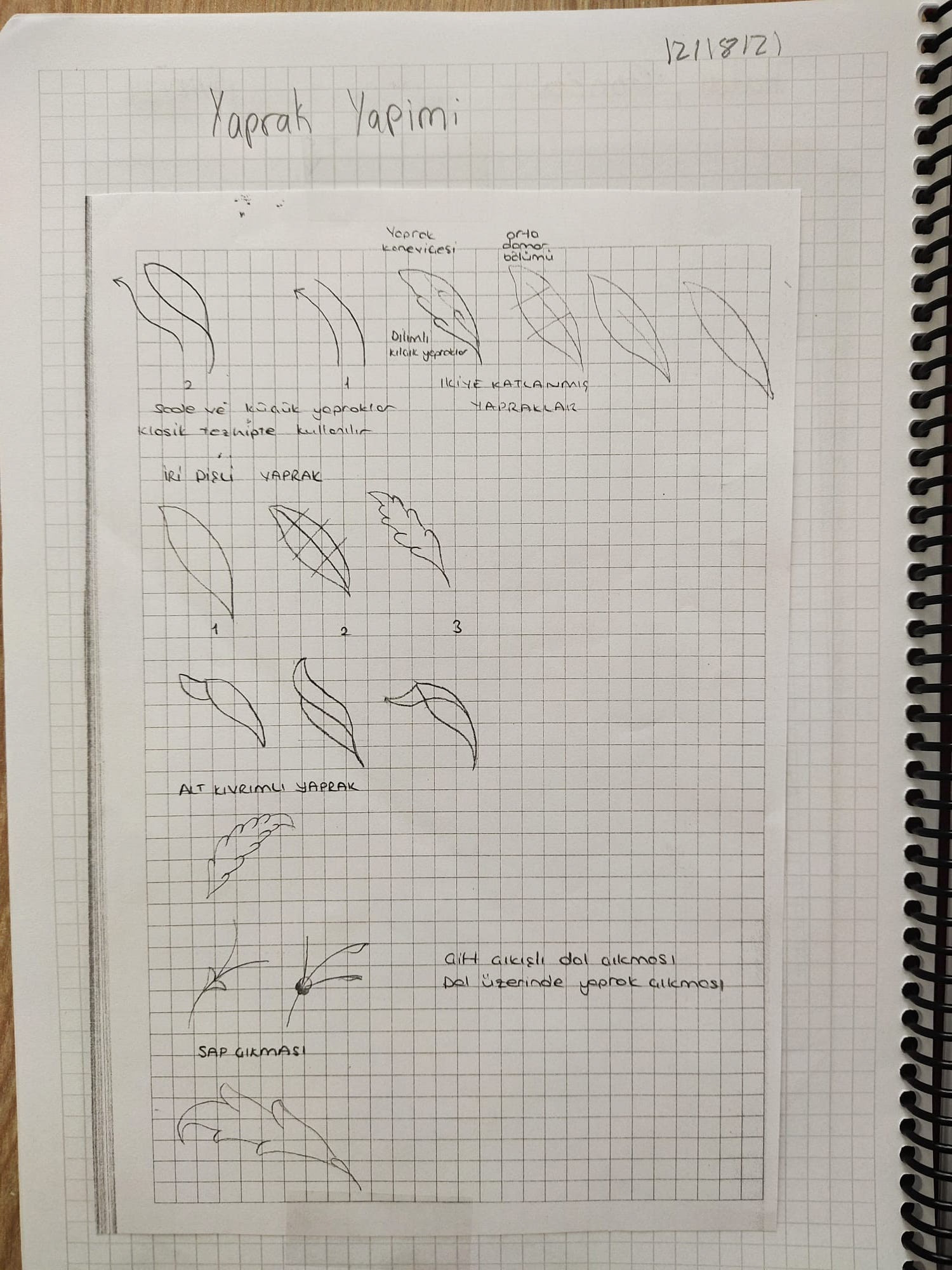

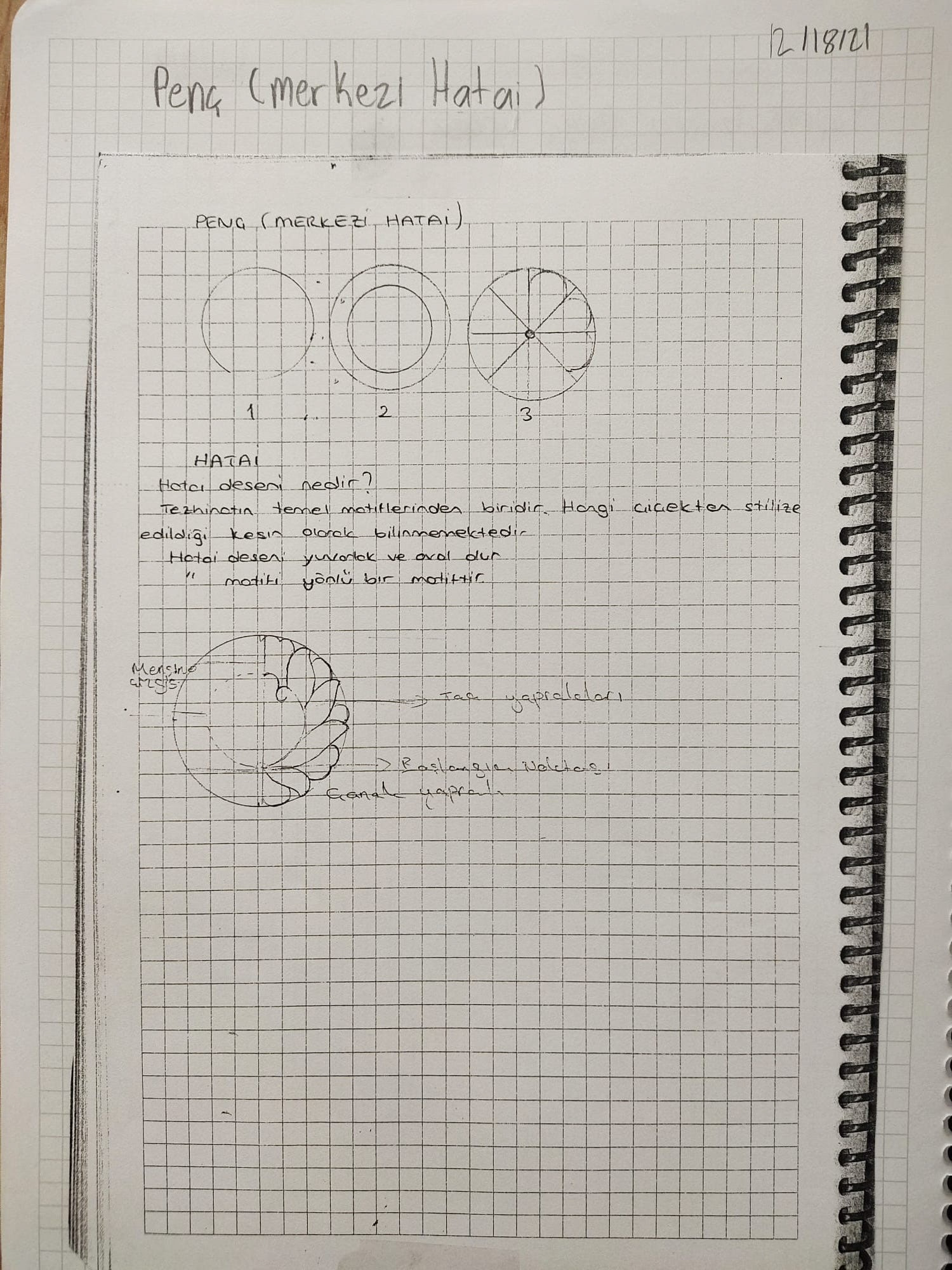

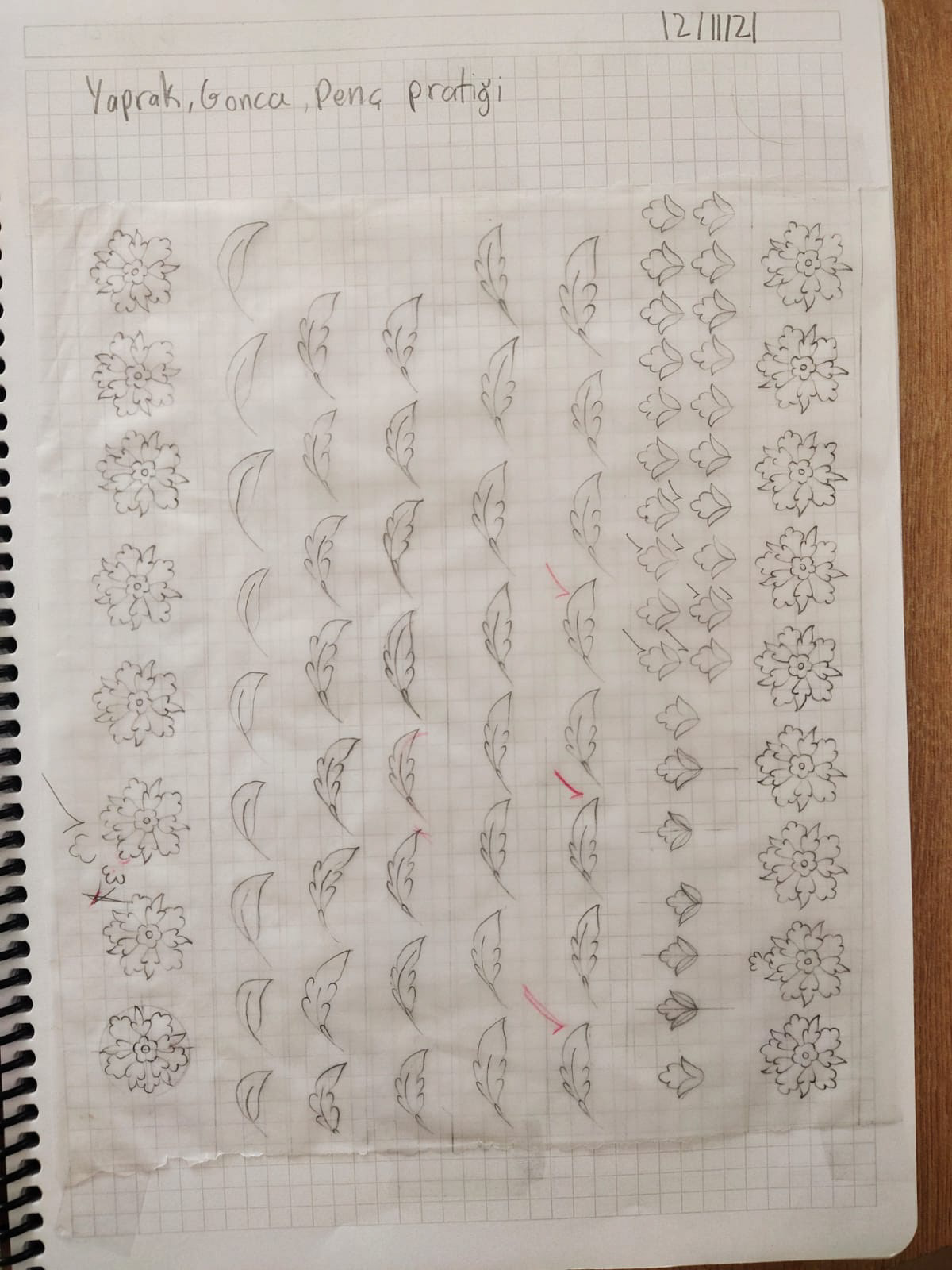

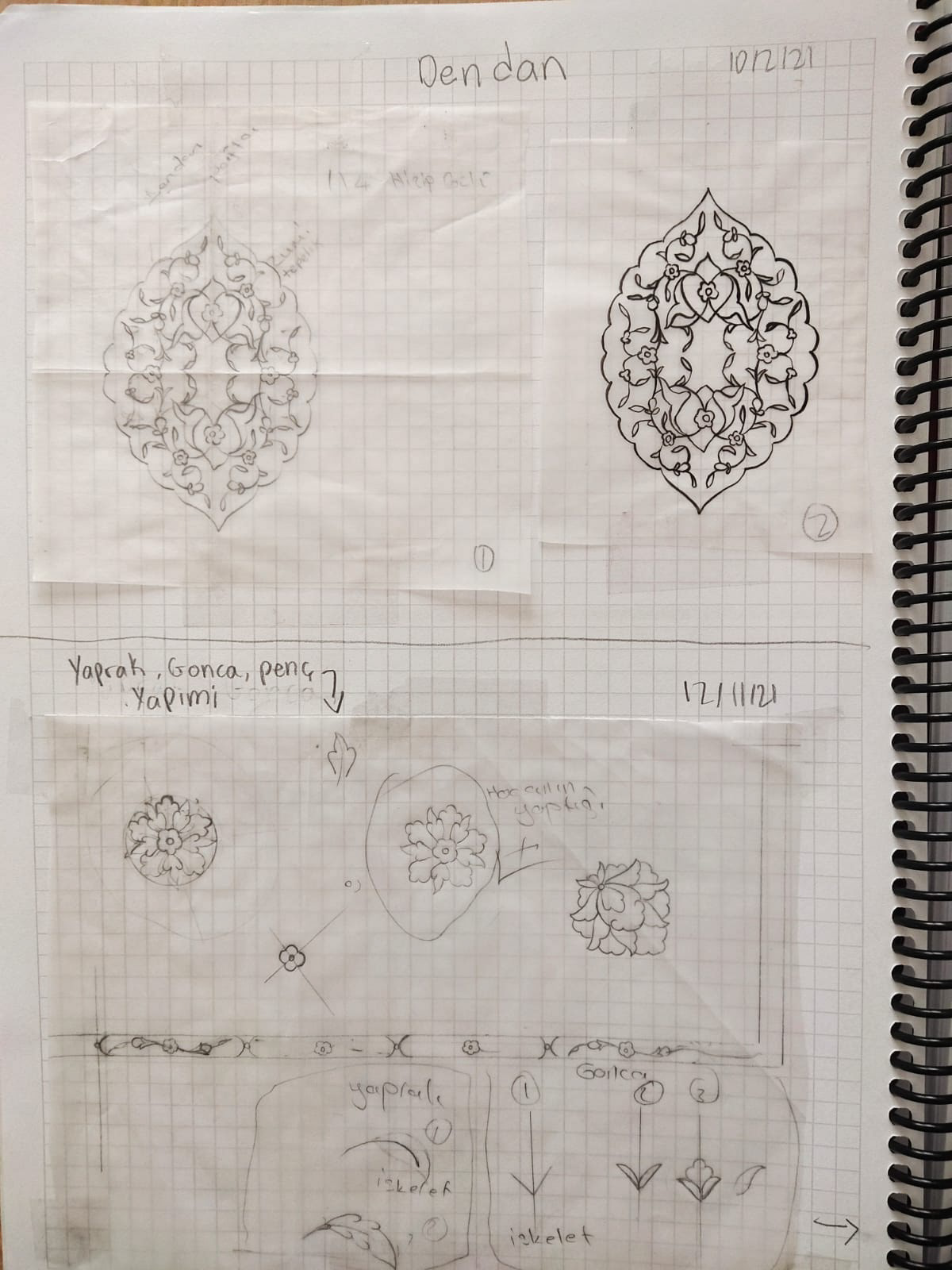

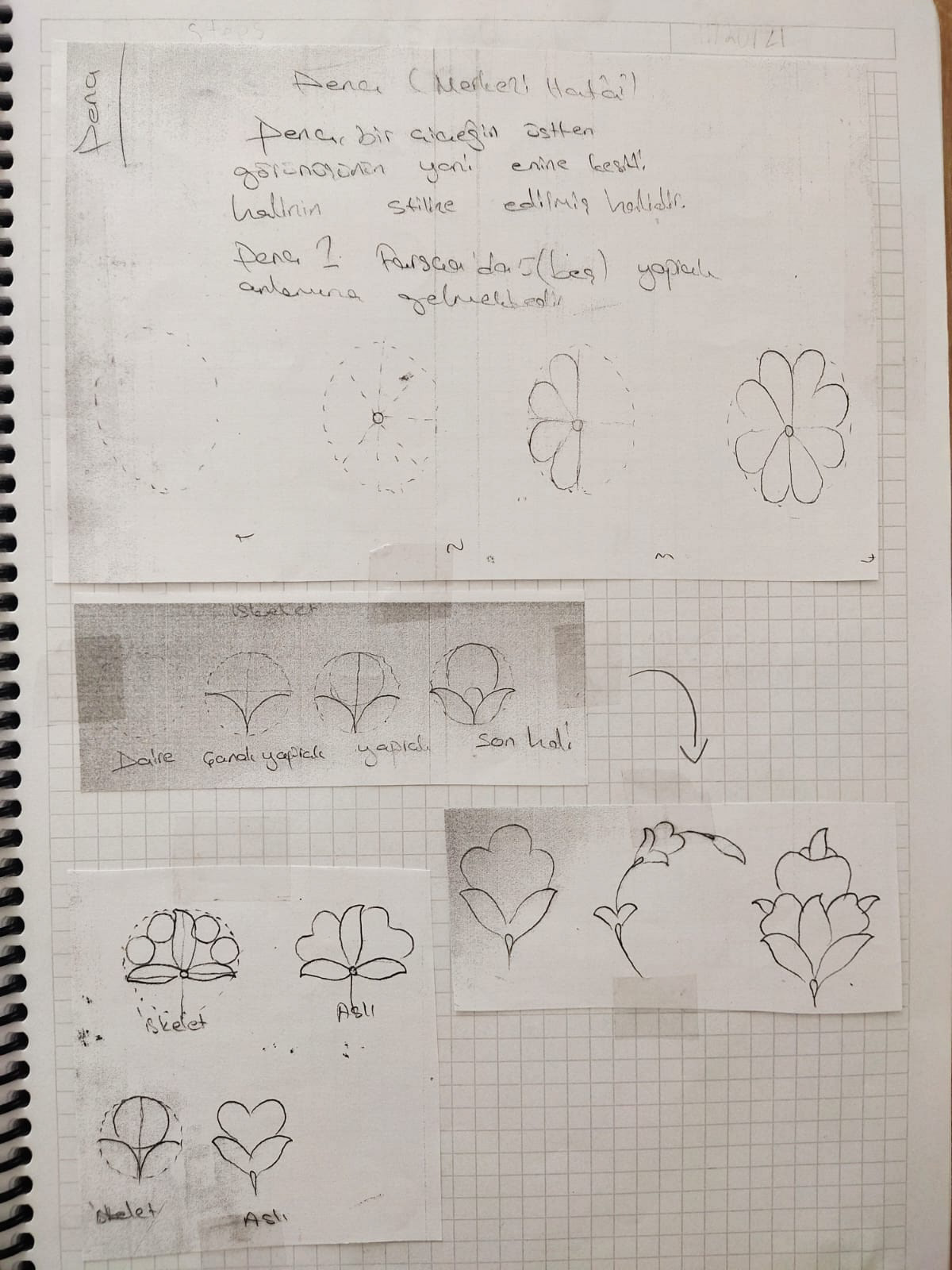

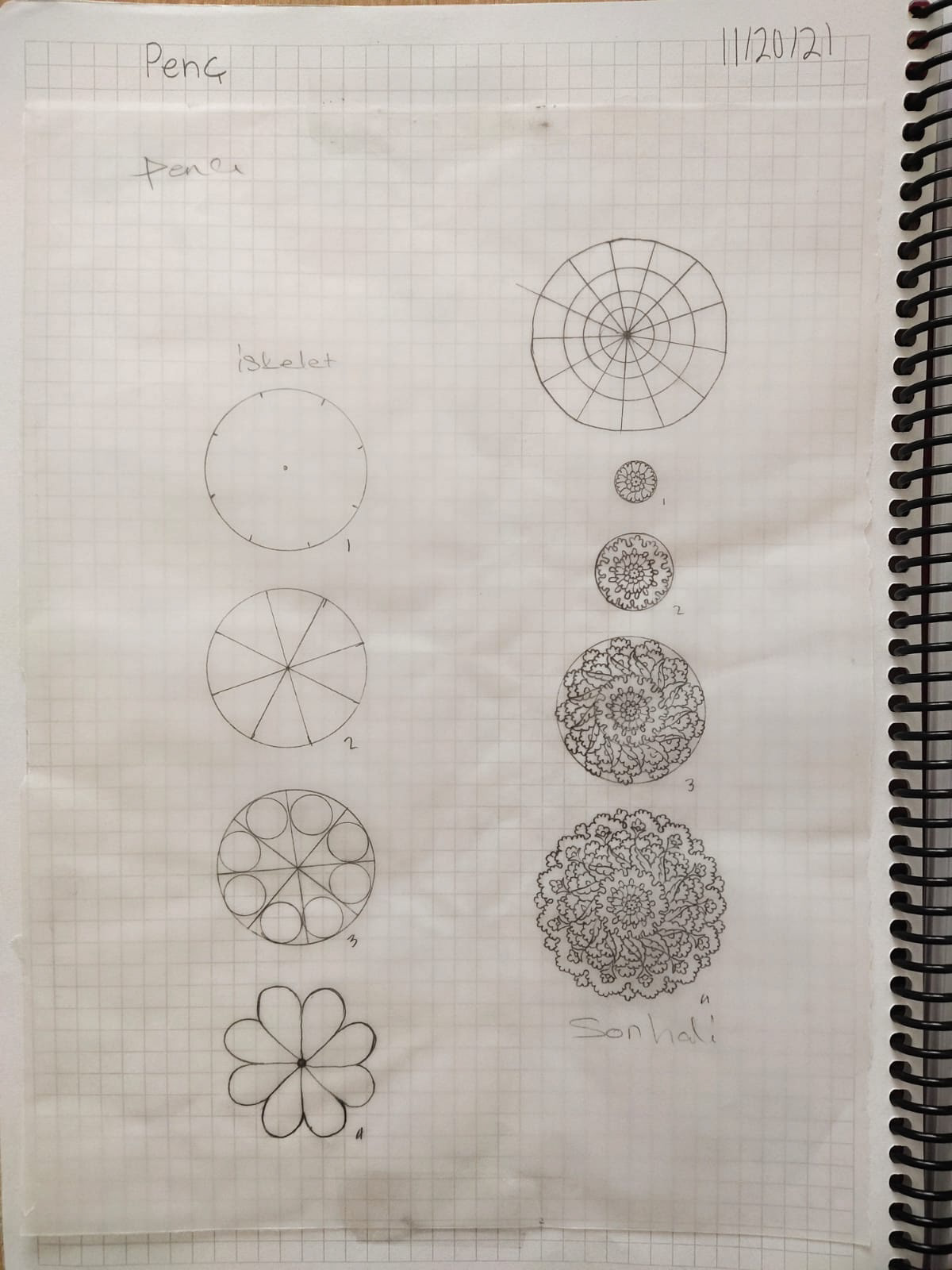

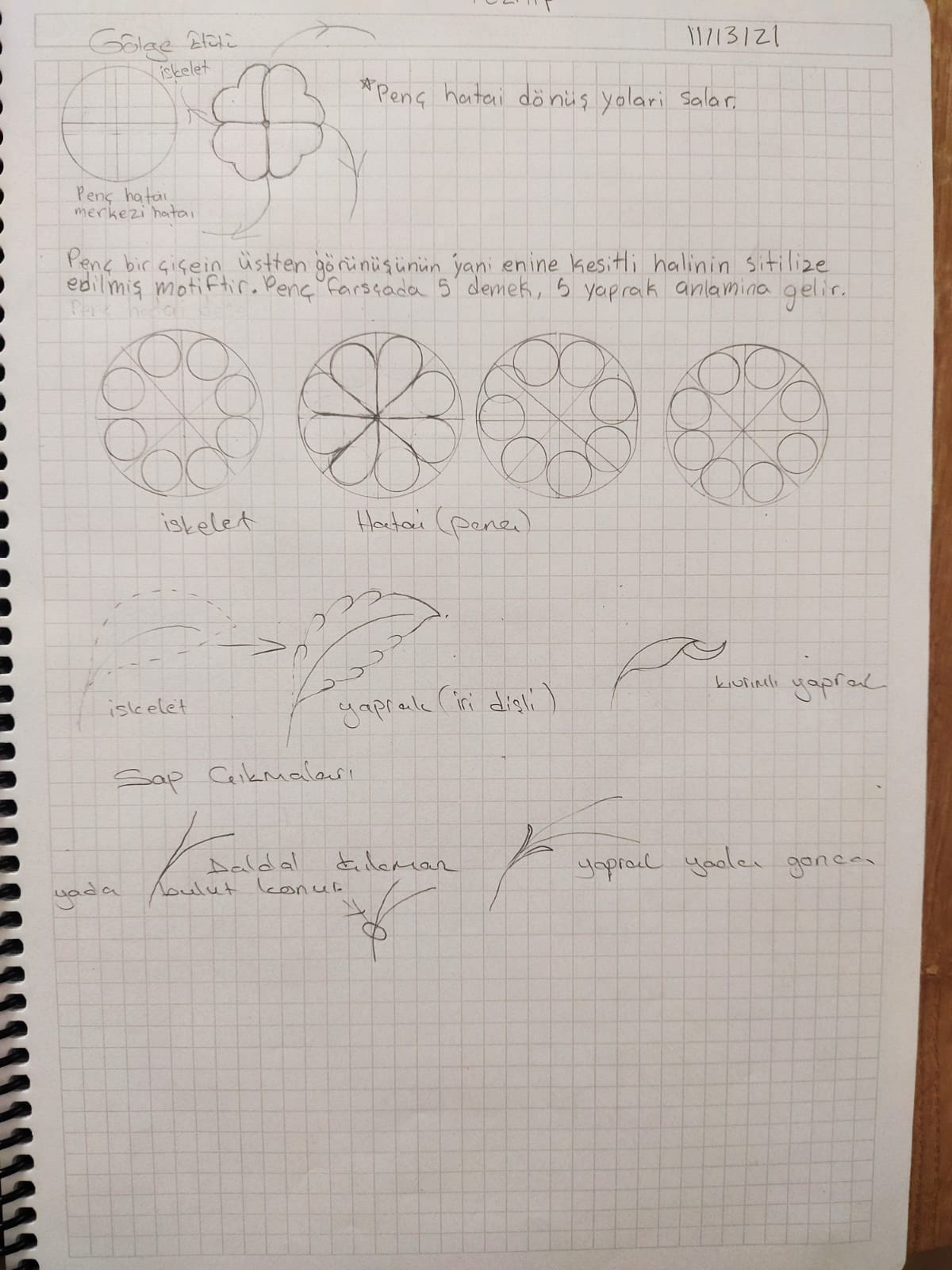

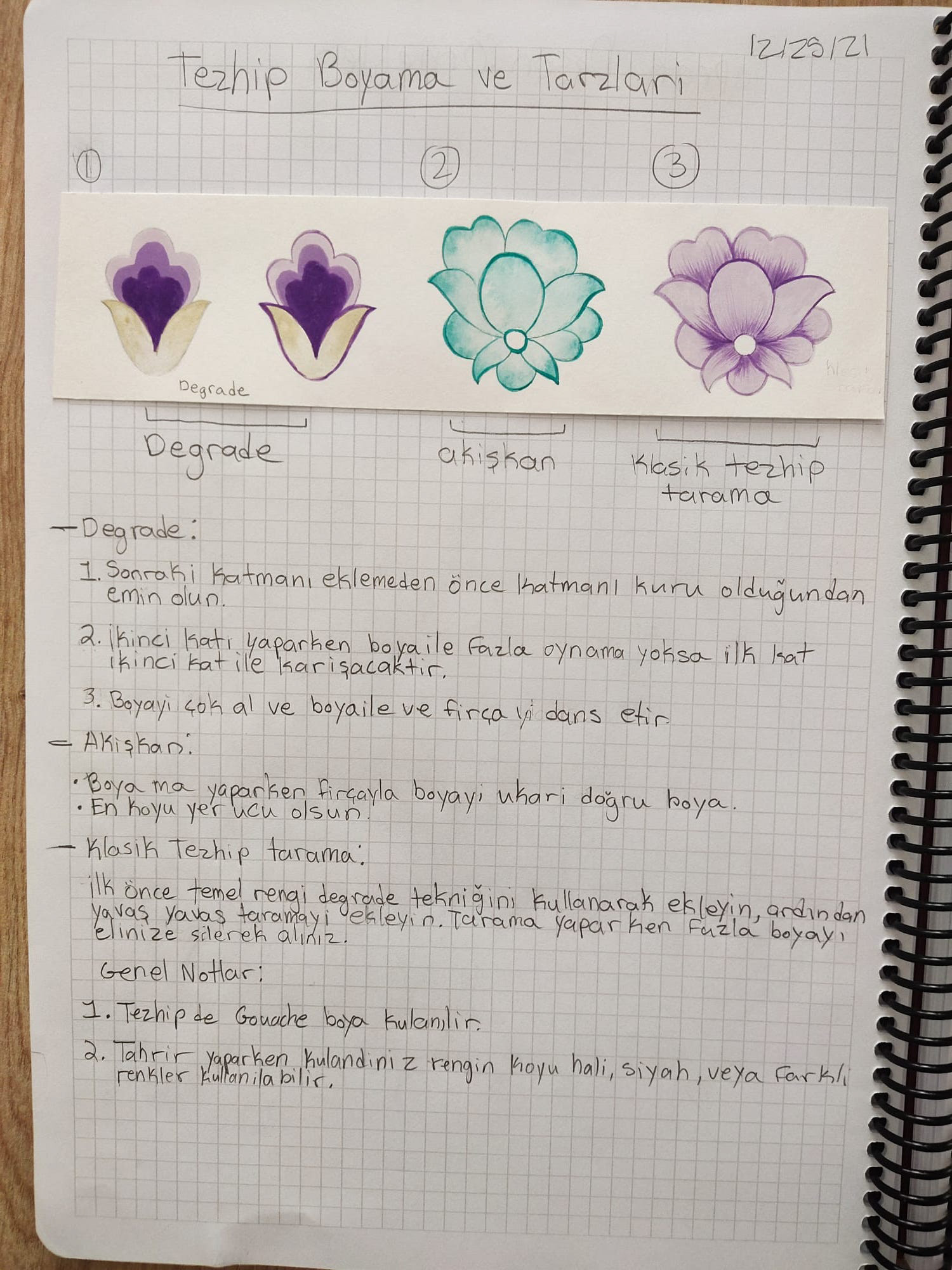

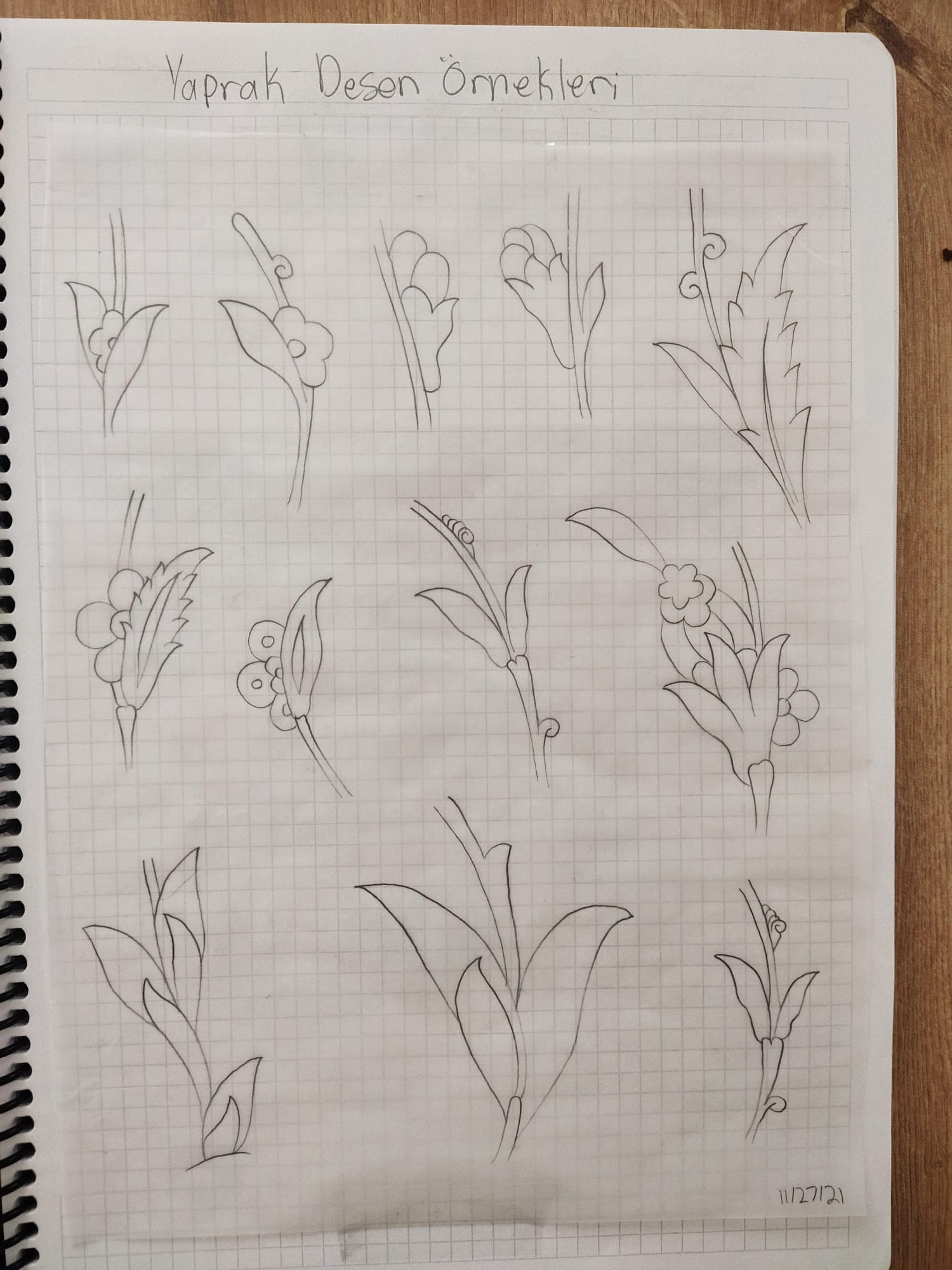

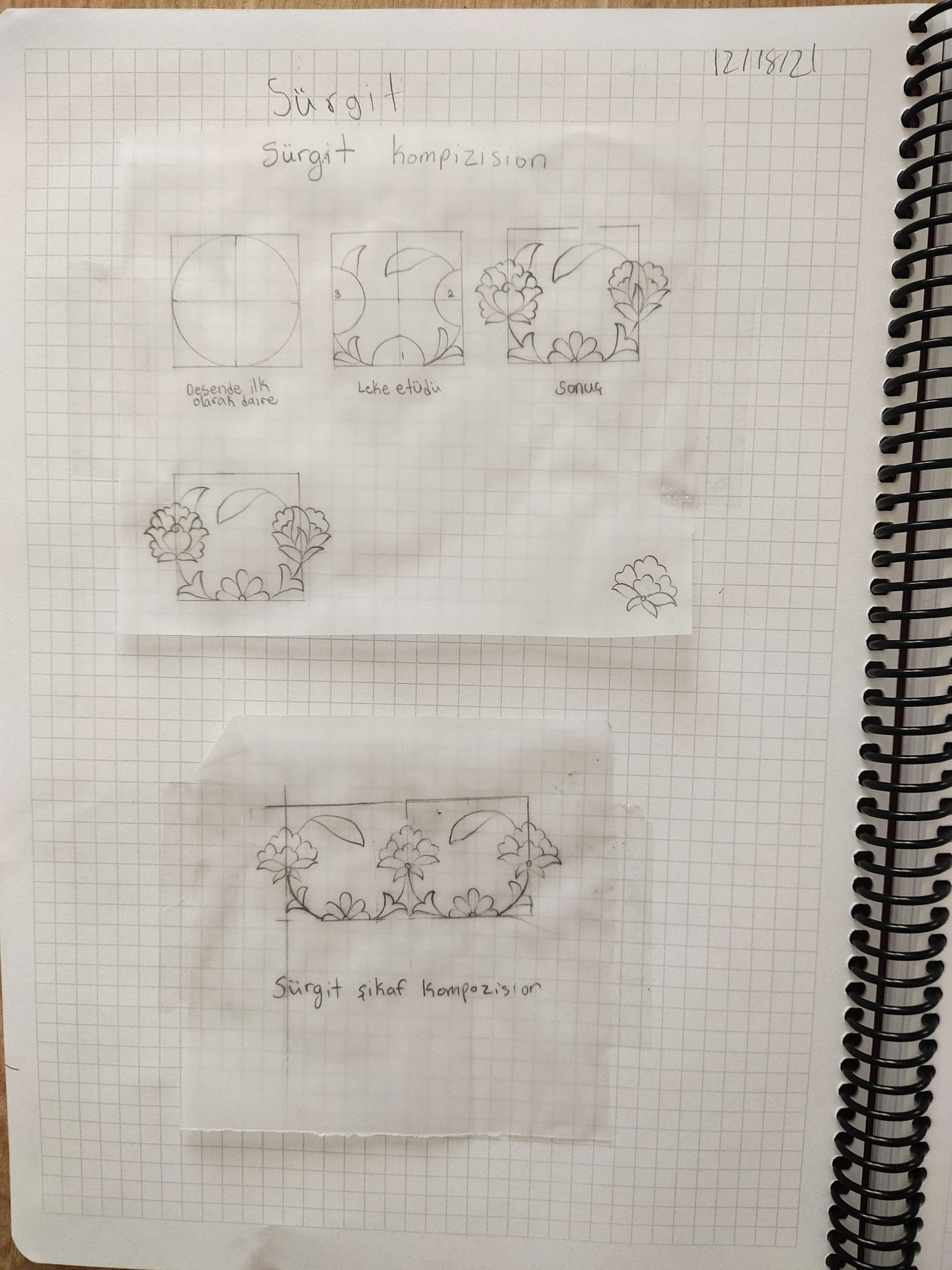

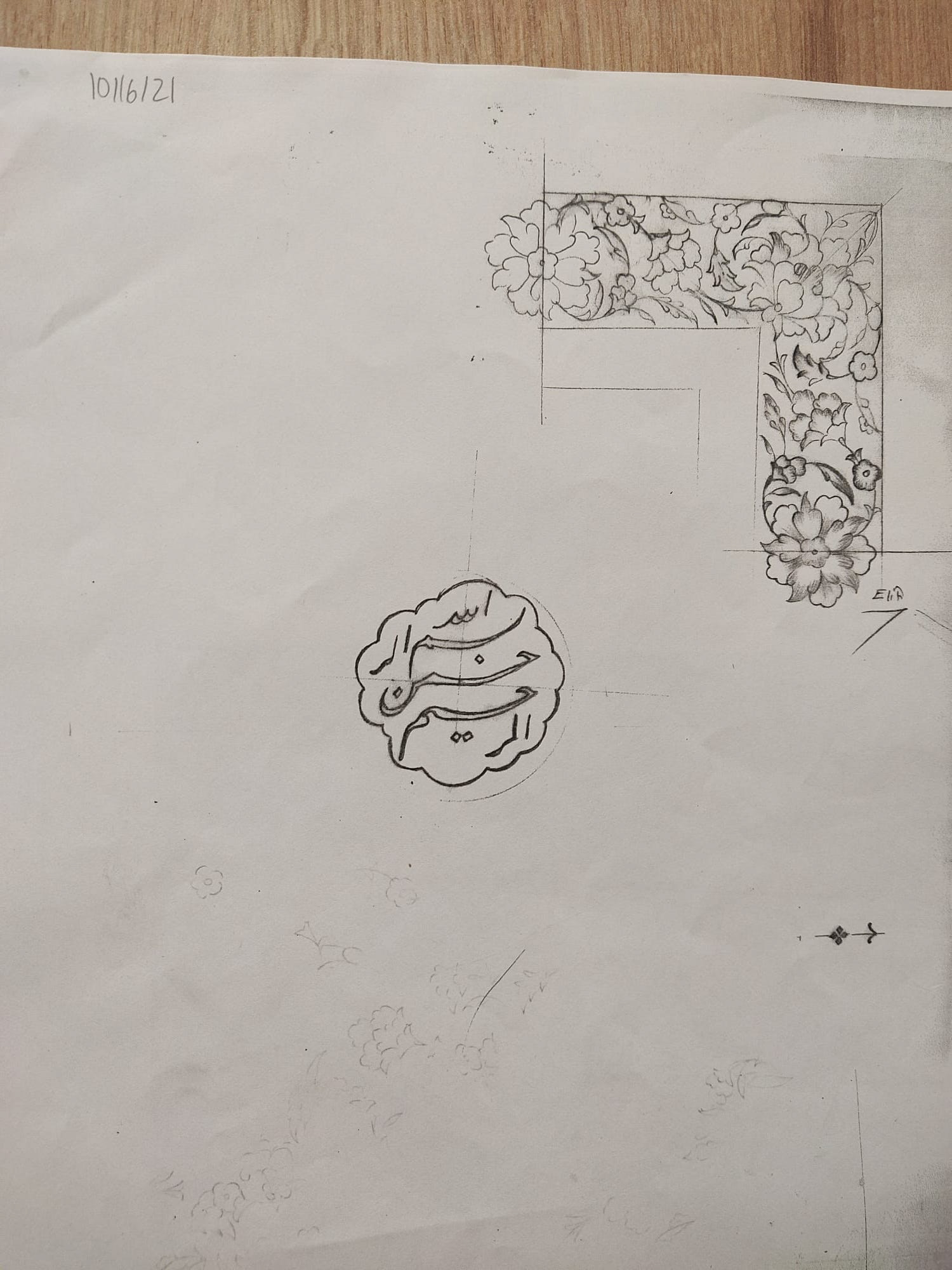

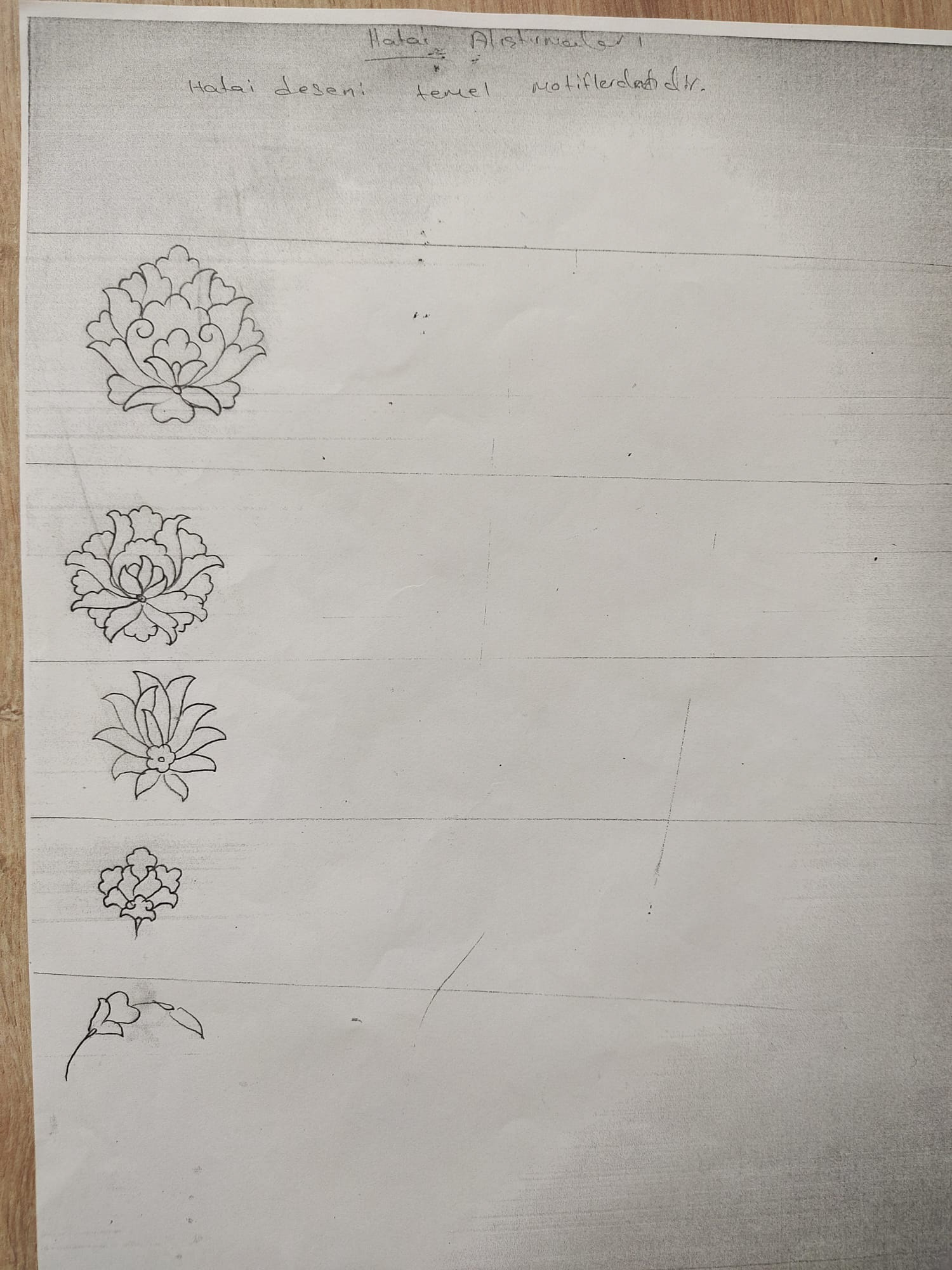

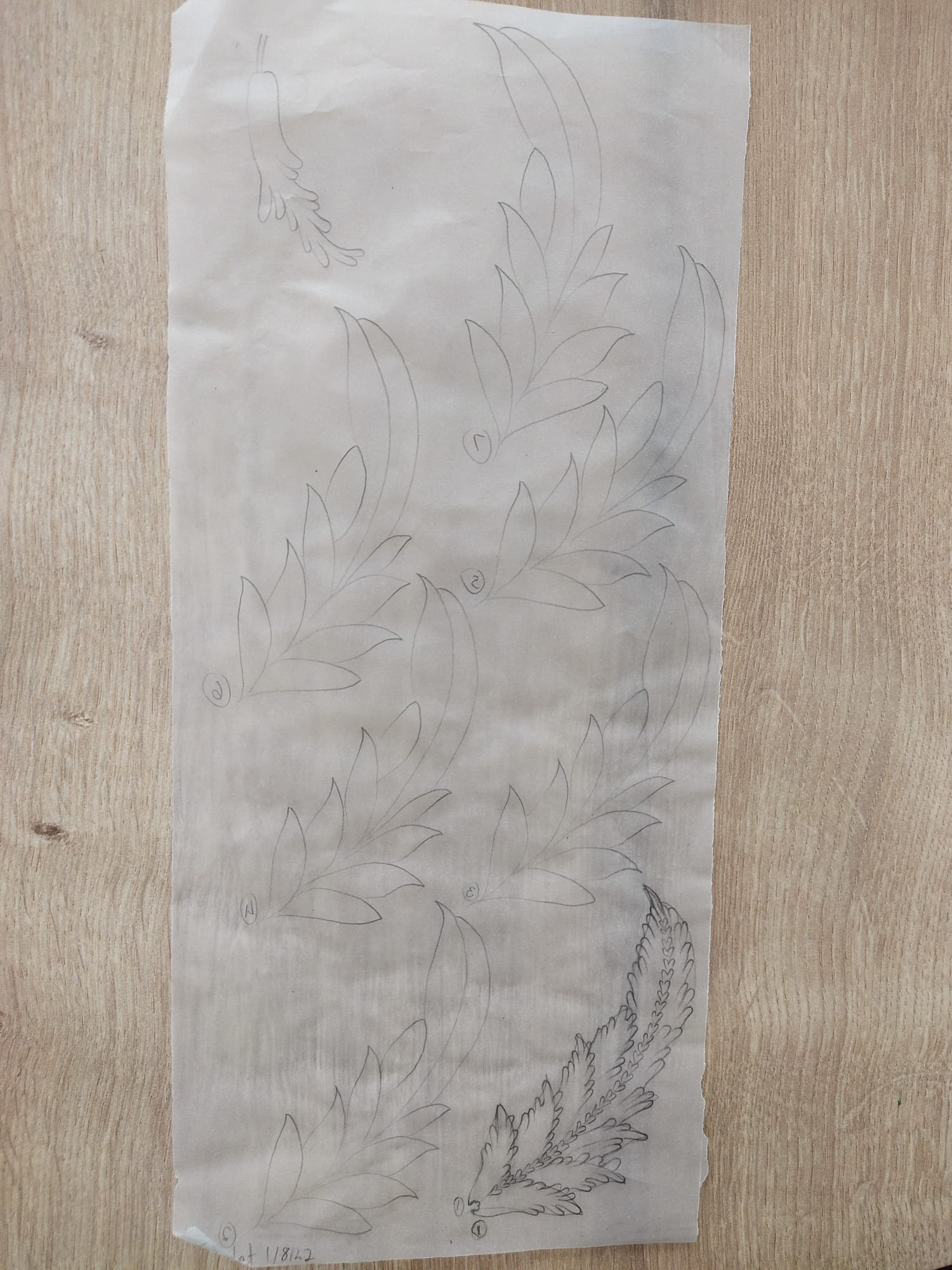

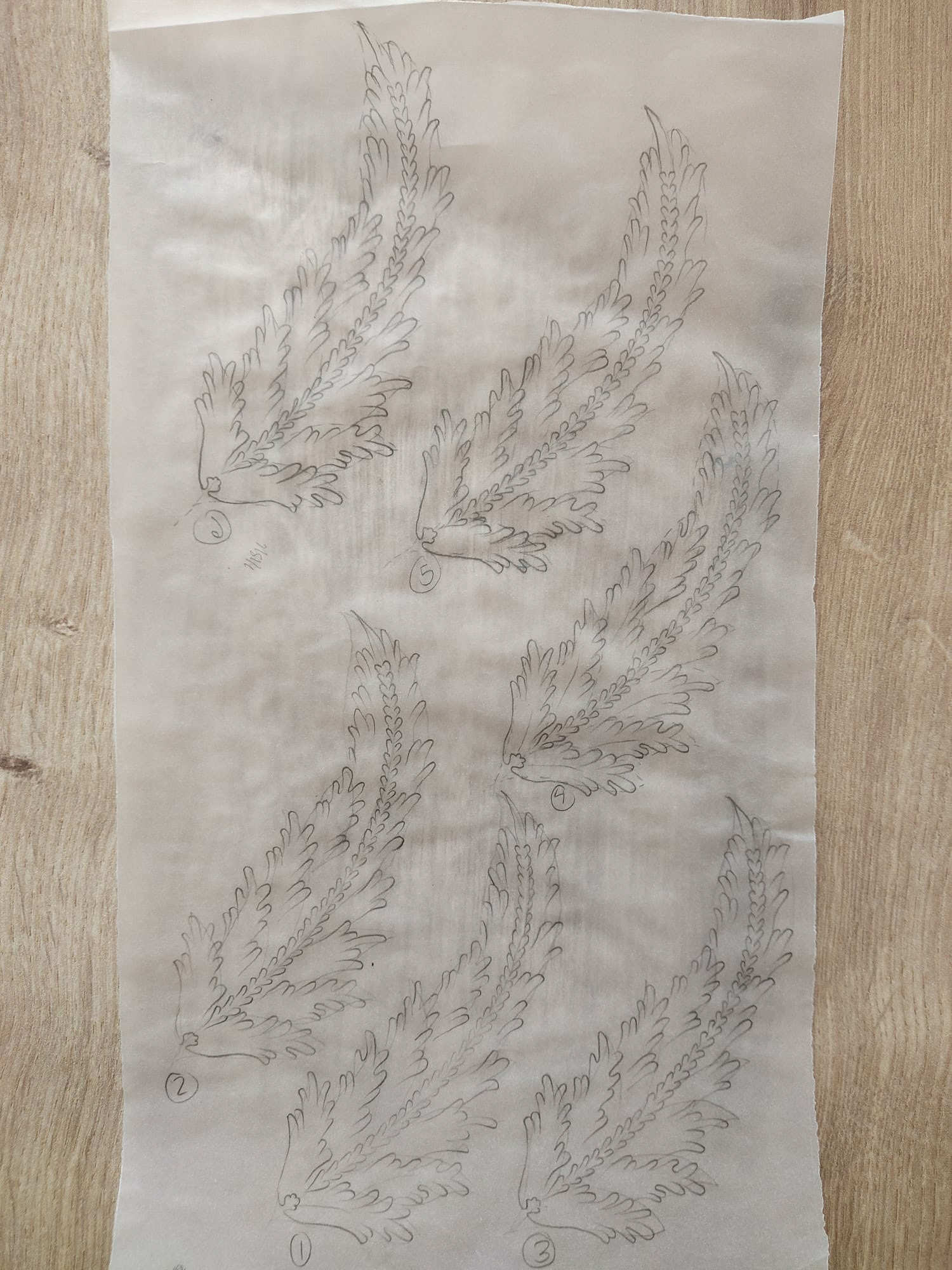

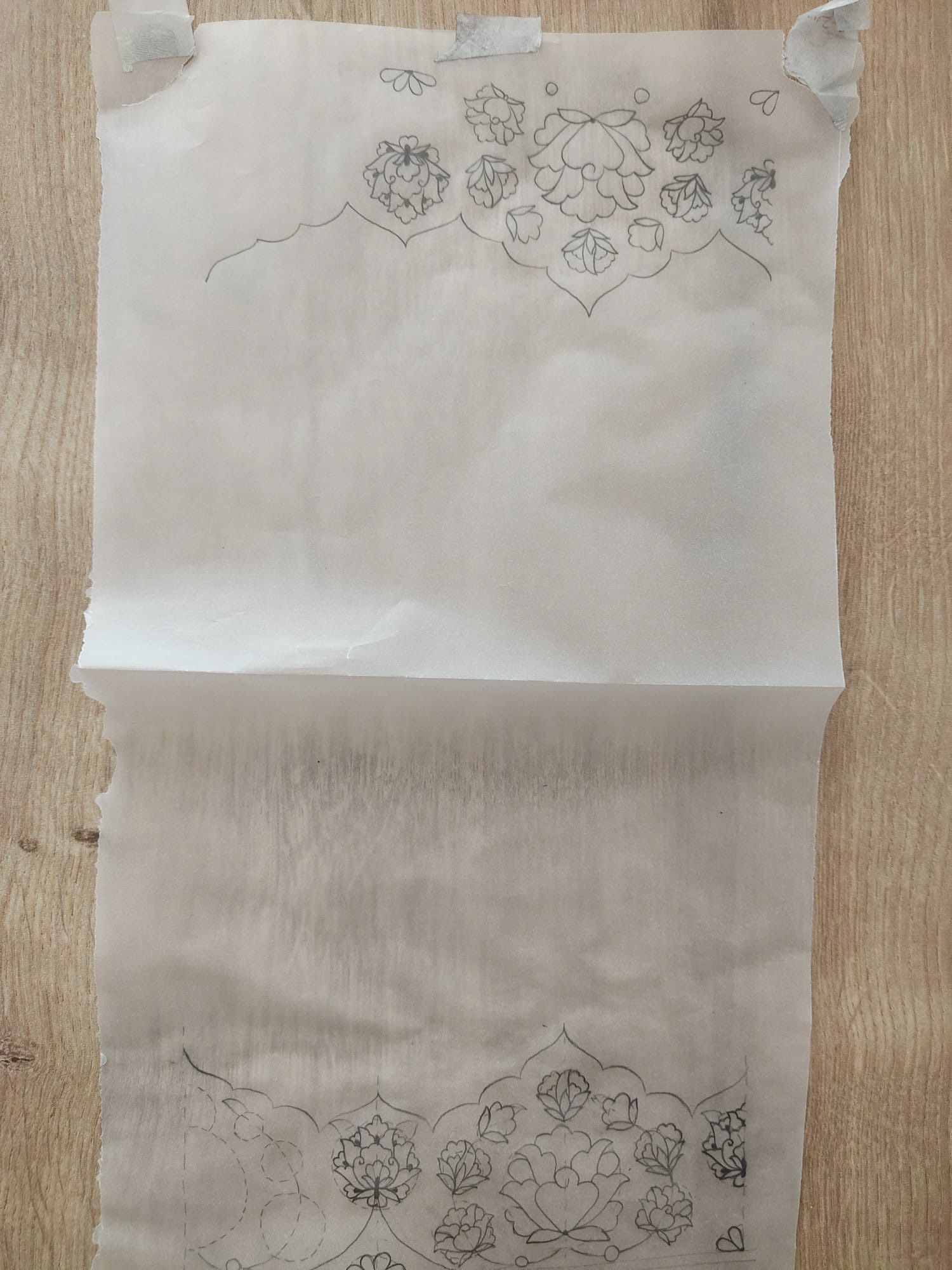

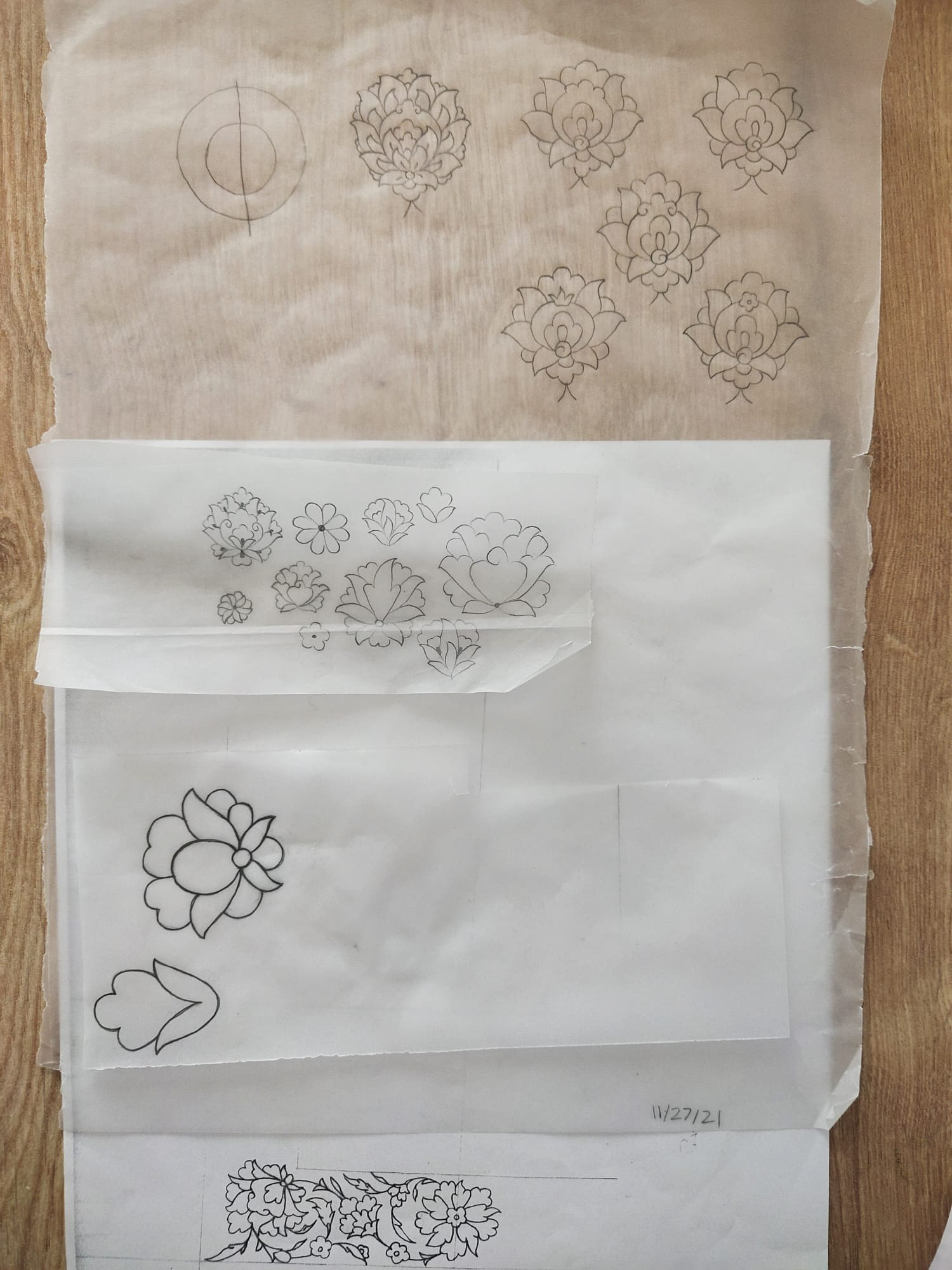

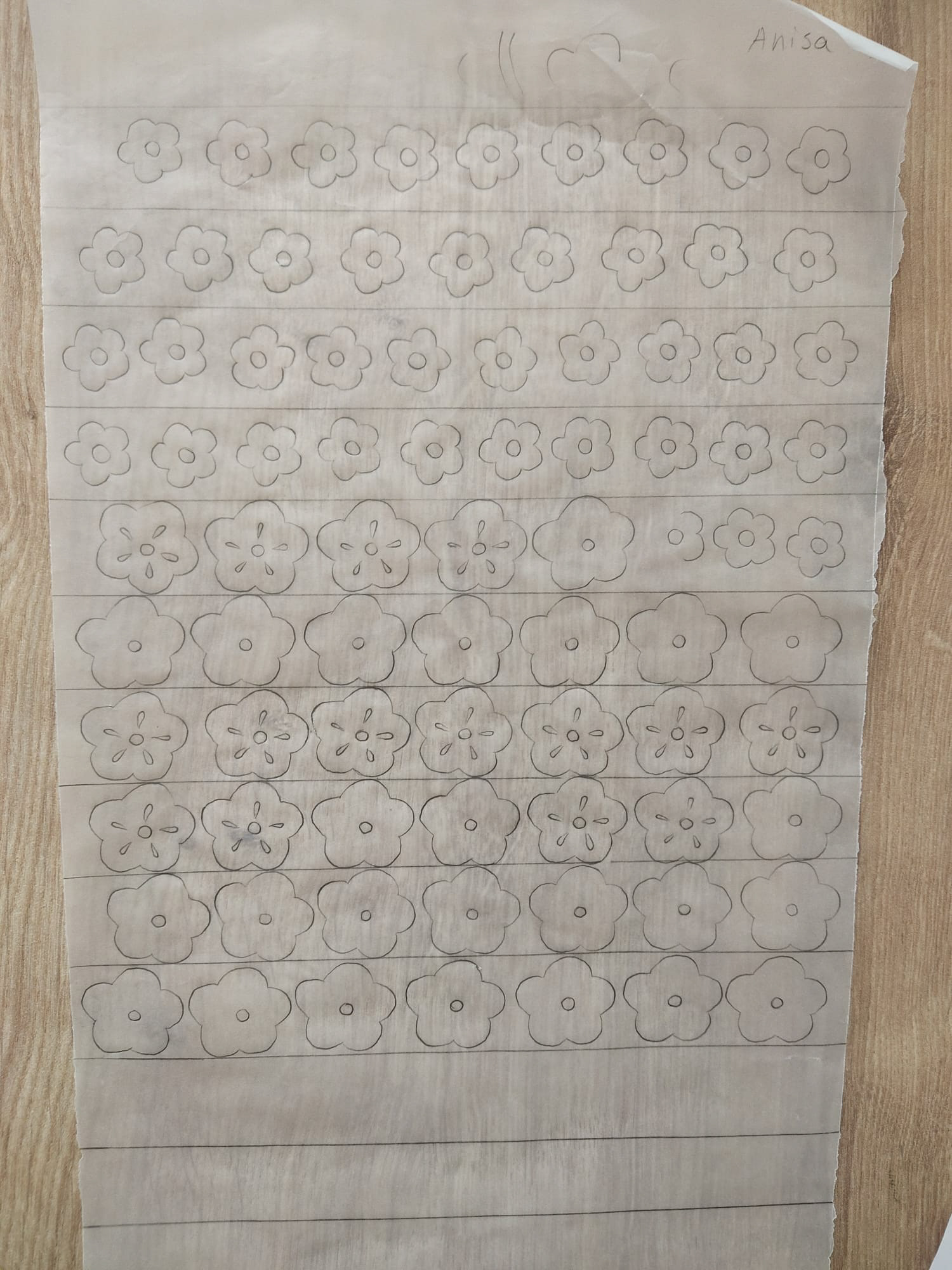

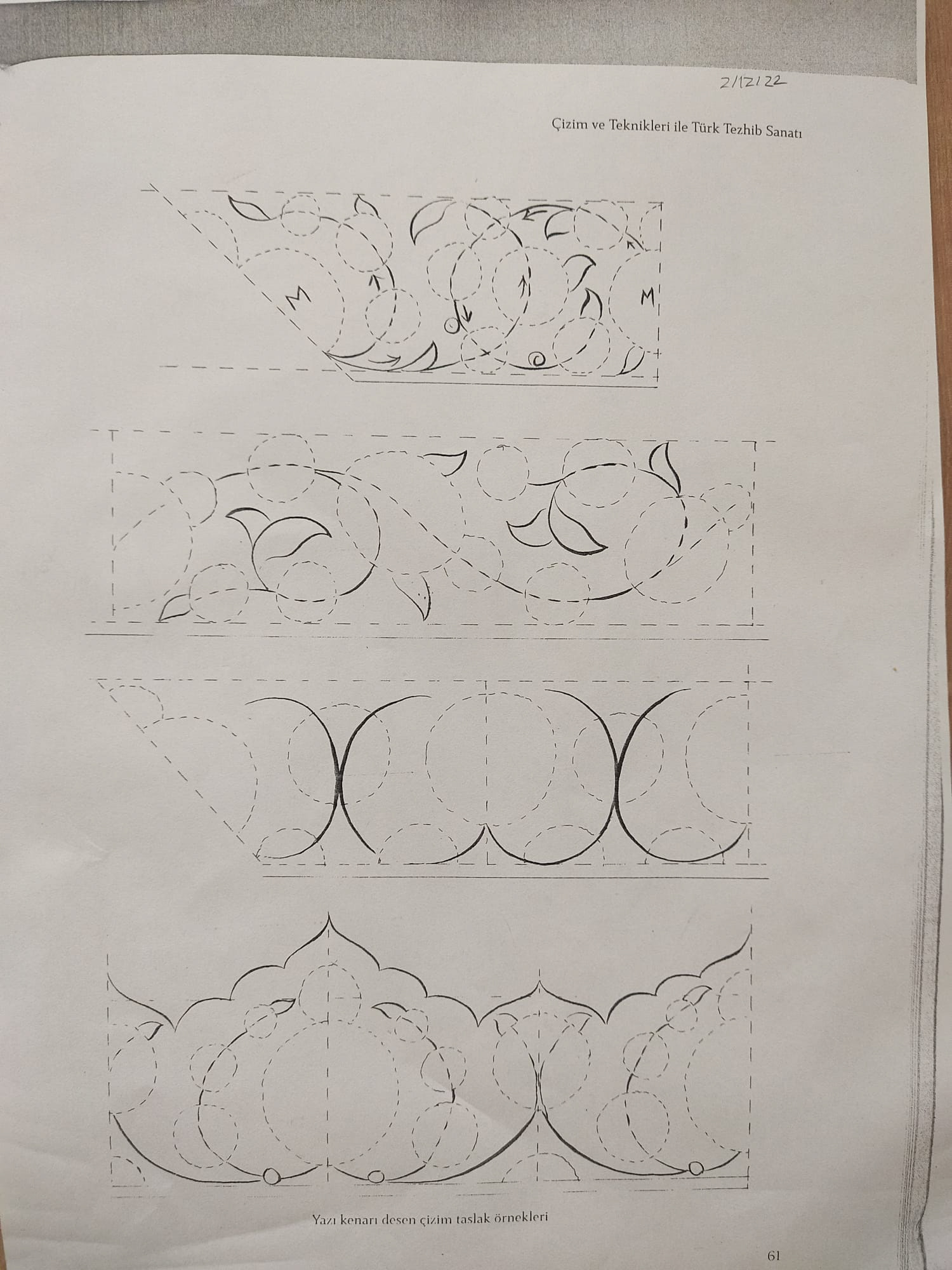

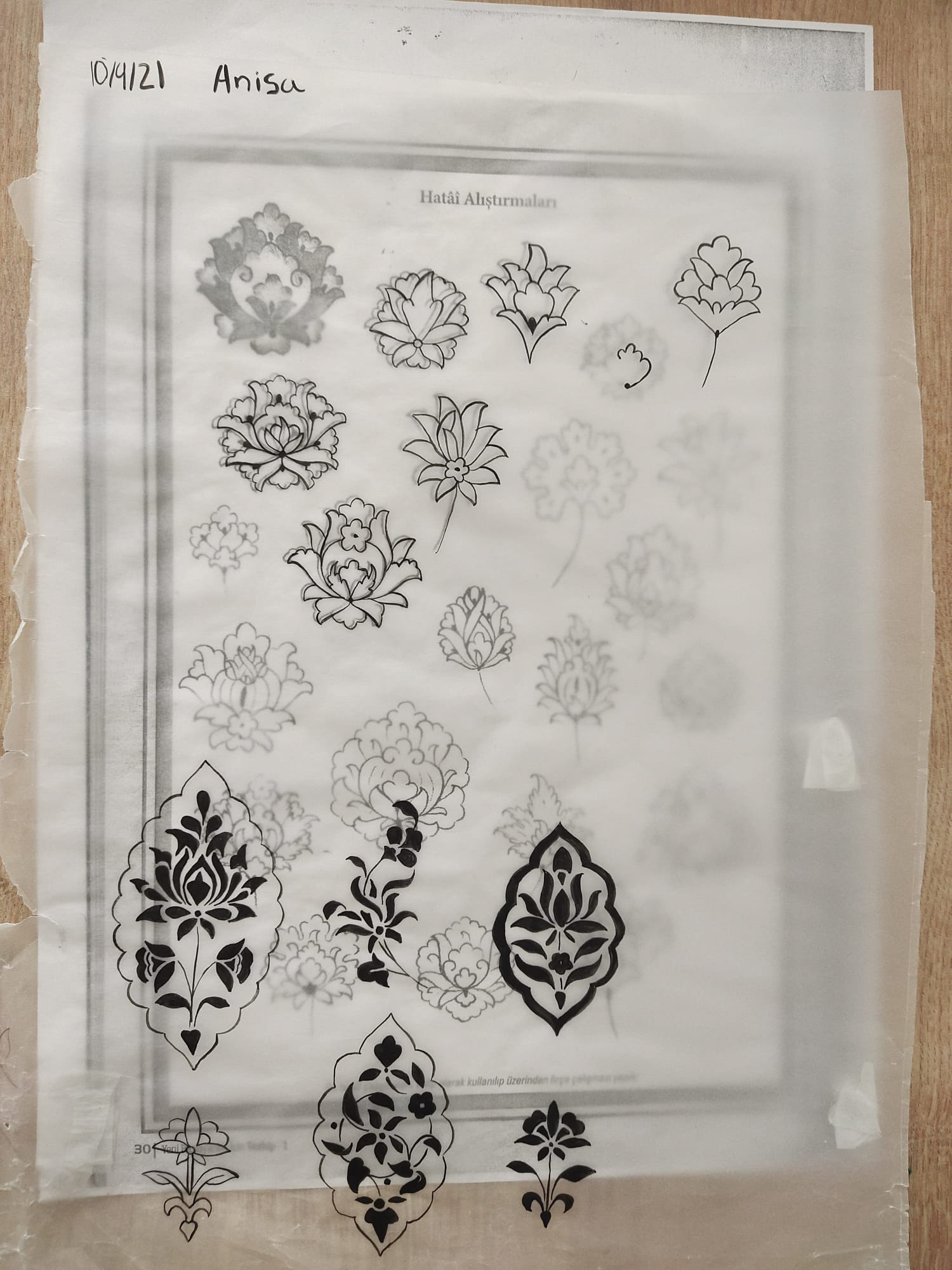

Anisa's Tezhip Practices

TEZHIP Practises by Anisa Ozalp

TEZHIP Practises by Anisa Ozalp

TEZHIP Practises by Anisa Ozalp

TEZHIP Practises by Anisa Ozalp

TEZHIP Practises by Anisa Ozalp

TEZHIP Practises by Anisa Ozalp

TEZHIP Practises by Anisa Ozalp

TEZHIP Practises by Anisa Ozalp

TEZHIP Practises by Anisa Ozalp

TEZHIP Practises by Anisa Ozalp

GOLD BEATING PROCESS FOR TEZHIP

Materials: Notebook, Gold leaf, A wide, cornerless glass dish, Strained honey (or Arabic gum), Distilled water

Step-by-step process:

1. Prepare your workspace by ensuring your hands are clean and free of creams or substances.

2. Place a drop of strained honey in the middle of the wide glass dish.

3. Take a sheet of gold leaf from the notebook and gently touch it to allow it to stick to your hand.

4. Begin crushing the gold leaf by rubbing it between your fingers and palm. Continue crushing for approximately 10 to 15 minutes.

5. As the honey dries, add distilled water to the dish instead of more honey to prevent excessive stickiness.

6. The gold leaf will transform into small particles and eventually a fine powder during crushing.

7. Allow the crushed gold to spread naturally in the dish.

8. Once all the gold leaf sheets from the notebook have been crushed, the dish will contain a mixture of gold particles and honey.

9. Separate the gold from the honey by adding distilled water to the dish and stirring. The gold particles will move in the water, while the honey will settle at the bottom.

10. Carefully pour off the clear water on top, leaving the gold particles at the bottom of the dish.

11. Transfer the remaining gold particles to a small dish for further use or storage.

12. Allow the gold particles to settle in the small dish.

13. The next step would be transferring the gold particles from the small dish to another surface or container.

14. After allowing the gold to settle and removing the clear water from the top, you will see the gold particles sticking together in the dish.

15. Transfer the gold particles to a smaller dish to make it easier to work with. This can be done by carefully pouring the gold particles into the smaller dish.

16. To prevent the gold particles from sticking to the sides of the smaller dish, add distilled water to the dish. This will help create a smooth surface for the gold particles.

17. Gently stir the mixture in the smaller dish to ensure the gold particles are evenly distributed and to prevent them from clumping together.

18. Once the gold particles are well-distributed in the water, carefully pour off any excess water, leaving the gold particles in the smaller dish.

19. The gold particles are ready for further use at this stage. You can apply them directly to your desired artwork using a brush or other appropriate methods.

20. If you want to store the gold particles for later use, allow them to dry completely. This can be done by covering the smaller dish and letting it sit for approximately 2-3 hours, allowing the excess water to evaporate.

21. Once the gold particles have settled and the water has evaporated, the remaining gold can be used as desired by directly applying it or packaging it for future use.

CIHANOGLU SOCIAL COMPLEX

Anisa began her journey in 2021 at Cihanoğlu Külliye in the Köprülü District of Aydın. The term "külliye" refers to a common social complex during the Ottoman Era. Cihanoğlu Külliye, built in 1756 by Cihanzade Müderris Abdülaziz Efendi, is an important example of the Ottoman Baroque style. Its square-plan units feature masonry walls, wooden roofs, and an opening to the courtyard with a low-arched door and rectangular window.

CİHANOĞLU KÜLLİYESİ in AYDIN

Techniques and Historical Context of Tezhip Illumination*

1. SHADED AND SCATTERED HALKARI TECHNIQUE

This process involves creating a shading effect with a brush. Gold droplets are added to leaf tips and gradually dispersed to the rest of the leaf. The key to this technique is decreasing the density of the gold particles the further they get from the tip. Although it requires significant time and effort, the brush strokes must remain invisible.

2. VARIATIONS OF HALKARI

The real charm of Halkârî becomes evident after the final sealing process. Various techniques like Tahrirli halkâri, colored halkâri, semi-transparent halkâri, and halkâri with painted motifs are utilized. Tahrirli halkâri highlights the design against a light-colored backdrop, while semi-transparent halkâri uses semi-transparent ink. The painted motif halkâri technique needs two layers and, therefore, twice the time to complete.

3. AIRED TECHNIQUE

This process involves drawing decorative lines in parallel at equal intervals. Also referred to as 'havalı' [Aired] due to the space between the lines, this technique requires that the spacing is visually comfortable and in proportion to the size of the motif. Usually, two contrasting colors are used against the background, with small and simple motifs.

4. GOLD SPRINKLING TECHNIQUE

Also known as "sieve-based scattering," aks. [Zer-efşan -Altın Serpme] This technique involves putting gold leaf into a sieve-like box and using a dry brush to make the gold particles fall onto a pre-moistened surface. Another variant artists employ is the brush scattering technique, where gold particles are combined with water, picked up with a brush, and sprinkled onto the surface.

CONCLUSION AND HISTORICAL CONTEXT

As a visual representation of divine words, the art of calligraphy has been deeply revered across the traditional world. Tezhip aims to convey this divine word through intricate compositions, creating works that further disclose it to captivate the audience. Even though the art of tezhip, complementing calligraphy, traces its origins to the 7th century, Its full bloom and fusion with writing occurred during the Ottoman era in the late 15th and 16th centuries. Tezhip art incorporates many motifs, including stylized motifs such as Rûmi, hatai, and münhani, alongside various floral, arboreal, and geometric designs.

* Techniques and Historical Context of Tezhip Illumination: Inspired by Article of Edip Yilmaz and Rumeysa Şimşek

REFERENCE LETTER

To Whom It May Concern, As Anisa's Tezhip teacher, I have observed her exceptional abilities as an artist. She possesses a keen perception and has demonstrated a strong aptitude for hand skills. Anisa has a natural talent for composition, and her pencil drawings and color perception are truly impressive. In addition to her artistic talents, Anisa is a pleasure to work with. She is respectful and compatible with her surroundings, making her a joy to teach and be around. I do not doubt that Anisa has the potential to excel in various fields within the fine art industry. I wholeheartedly recommend her for any program or opportunity she may be seeking, and I believe she will make a valuable addition to any artistic community.Sincerely, MÜZEHHİBE ELİF AYDIN (December 29, 2022)

COMMISSION

Should you require innovative insights for your design ventures or are interested in commissioning art pieces, feel free to reach out to Anisa. She specializes in the Tezhip art form and is willing to contribute to your artistic projects. To gain a deeper understanding of her creative process, visit her YouTube Channel, where you can find speedpaint videos, among other informative content.

• ┈ ୨ ୧ ┈ •

ANISA TEZHIP WORKS ARE ALL ABOUT #TezhipJourney #IslamicArtRevival #OttomanManuscriptArt #TezhipTradition #ManuscriptIllumination #GoldGildingArt #AnisaTezhipArtist #CihanogluKulliyesi #UyghurHeritage #MüzehhibeArt #CommissionedTezhip #TezhipTutorials #ModernMeetsTraditional #HandcraftedIllumination #TezhipExhibition